Providing financial assistance to homeless people should be a source of pride. It shows that we are a civilised society prepared to act to protect people from losing their homes. Despite some shifts in public attitudes regarding who should receive welfare benefits, there is still strong public consensus favouring this kind of social protection.

Homeless people face a welfare system that is a fragmented safety net. Some get the help they need to pay for housing costs, others may get limited, or no financial help at all.

But the safety net can be completed. In this chapter we start with simple principles – to end homelessness, those who cannot afford housing must be given enough assistance to do so. And adequate support must be available to help homeless people into work where it’s appropriate for them.

A joined-up approach to support with housing and employment will help to prevent future homelessness for people at risk, reduce the chances of repeat homelessness, and help homeless people into work.

Financial support through the benefits system is crucial in preventing homelessness. It provides low-income households with protection and stable housing. For people who are already homeless, welfare assistance with housing and other costs is a lifeline that helps them leave the devastation of homelessness behind.

Universal Credit, which was introduced in 2013, is the most significant welfare reform in decades. It creates an opportunity to ensure the benefits system works effectively to prevent and respond to homelessness. It is ambitious – its intention is to create a welfare system that helps people achieve financial stability and employability wherever possible.

Universal Credit aims to simplify the current system by bringing together six different benefits (including Housing Benefit) into one single monthly payment. It is also intended to make transitions into work easier and to make work pay.

While the intention behind Universal Credit is promising, a series of changes and falling investment since its original design have reduced entitlement to financial support for the people who need it most. The £1.5 billion package of support through the 2017 autumn budget was a welcome recognition of the additional support needed. This will go some way to reducing financial pressures, especially with housing needs, but there remain other areas in need of investment and policy change.

The reduced investment in the system has undermined the original design of Universal Credit. As a result, in its current form it fails to deliver a comprehensive safety net that adequately prevents and responds to homelessness. The situation has also been worsened by administrative errors and delays related to implementation.

People lose their homes when the rising pressure from high rents and low incomes becomes too much. Without government support, a sudden increase in pressure, like losing a job or becoming ill, can quickly force people into homelessness. The welfare system, including Universal Credit in its current form, is worsening the pressure leading to homelessness.

This undermines the efforts by the Westminster, Scottish, and Welsh Governments to tackle and prevent rising homelessness.

Below we explain how the welfare system can have a strong and complete role in responding to and preventing homelessness. We also clearly set out how the welfare system can support the joint goal of stabilising housing and helping people pursue employment.

Housing Benefit will no longer exist when Universal Credit is rolled out completely. However, support with housing costs in Universal Credit will be calculated in much the same way as Housing Benefit. So within this chapter, Housing Benefit and support with housing costs in Universal Credit are synonymous, unless stated otherwise.

The Housing Benefit system was introduced in 1987. Significant reforms to the system began in the early 2000s by the Westminster Government. A key change was the creation of Local Housing Allowance for tenants in the private sector, which was rolled out nationally in 2008.

Local Housing Allowance rates are a way of setting maximum entitlement to Housing Benefit based on the size of the property being rented. In 2009, this was up to a maximum of five-bedroom properties in an area. They were set at the median of rents within an area and the rates were uprated to reflect changes in the prices of local private rents.

Since Local Housing Allowance was rolled out, a rise in insecure and temporary employment, falling wage growth, and overall rising private rents, have meant that more households need support with housing costs.

From 1999/2000 to 2009/10, spending on Housing Benefit increased from £11 billion to just over £21 billion. Much of this spending was on Housing Benefit for social rents. However, increasing reliance on the private rented sector to house low-income households has also meant increased spending on Housing Benefit through Local Housing Allowance rates. A significant proportion of the overall increased expenditure was on working age households (from £7 billion to more than £14 billion).

In 2010, reducing the Housing Benefit budget was central to a package of welfare changes aimed at reducing public expenditure. Several cuts were introduced from 2011 to 2014.

These included the following.

From April 2011 to 2014, private rents grew on average by 6.8 per cent, whereas Local Housing Allowance rates over the same period increased by 3.2 per cent. This represented a gap of £6.84 per week between Local Housing Allowance rates for renters on Housing Benefit and the 30th percentile market rent levels. Gaps rose to around £100 a week in more expensive areas such as inner London.

The changes to Local Housing Allowance rates also made it harder for people to access homes in the private rented sector. While Local Housing Allowance was set to allow recipients to afford the bottom third of the market, it did not take into account demand for rents at these levels. Households in this bottom 30th percentile are competing with others reliant on Housing Benefit, people in low paid work, and in some areas, with students.

This meant in areas with insufficient supply of affordable accommodation, many renters receiving Housing Benefit were forced to rent accommodation with a gap.

Further reductions were announced by the Westminster Government in 2015. These included a freeze in Local Housing Allowance rates from April 2016 for four years until 2020. This has significantly worsened the gaps faced by tenants between market rents and the maximum amount of Housing Benefit they can receive. As shown in the following section, this has created severe affordability problems for low-income households in the private rented sector.

This section outlines the impact of Housing Benefit changes on private rented sector affordability for homeless people and those on low incomes. As discussed in Chapter 11, ‘Housing solutions to homelessness’, the private rented sector is increasingly relied upon as a solution to homelessness, particularly in England and Wales.

Our 2018 research with the Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) examined the cumulative effects of Local Housing Allowance changes on the ability of households with low incomes to find and afford private rented sector housing. These households included homeless and previously homeless people.

The research considered private rented sector affordability for working-age households when not in work, and when in part-time or full-time work at the National Minimum Wage. These households included: single people in shared accommodation; couples without children in one-bedroom accommodation; and small families with up to two children in two-bedroom accommodation.

We looked at affordability for households not in work to understand whether Local Housing Allowance rates are keeping up with private rents. This affects whether homeless households not in work can find stable housing.

We also looked at households in work to compare where the private rented sector was affordable with earned income. We wanted to understand how financially stable these households were and the impact of these levels of earnings on homelessness risk. So we looked at whether the private rented sector was affordable when working households aimed to have enough money left, after paying their rent, for essentials such as bills, food, and clothes.

We did this by comparing private rented sector affordability for households in work in three different situations. These were:

Households not in work

There are significant geographical differences between England, Scotland, and Wales regarding gaps between Local Housing Allowance rates and rental costs at the 30th percentile of the private rented sector. Such differences clearly affect whether homeless people not in work can afford housing.

Broadly, there is little affordability within Local Housing Allowance rates in the private rented sector across most of England. In Scotland, there are areas where affordability within Local Housing Allowance rates is a significant challenge. In Wales, there are more options within Local Housing Allowance rates, assuming no issues with the amount of accommodation available.

In England, the effect of the reductions to Local Housing Allowance rates means very little of the private rented sector is affordable within the current rates. This is even in regions where housing is typically more affordable.

Initially, the effect of the reductions was severe in London and the South East; here, households looking to rent within Local Housing Allowance rates were struggling most. As the reductions continued, this severity expanded to include significant parts of the East of England and the South West. The research for 2018 shows us that now, households will struggle to afford housing within Local Housing Allowance rates in all regions in England. The exceptions are: the North East, half of the areas in the North West, and a couple of areas in the South West of England.

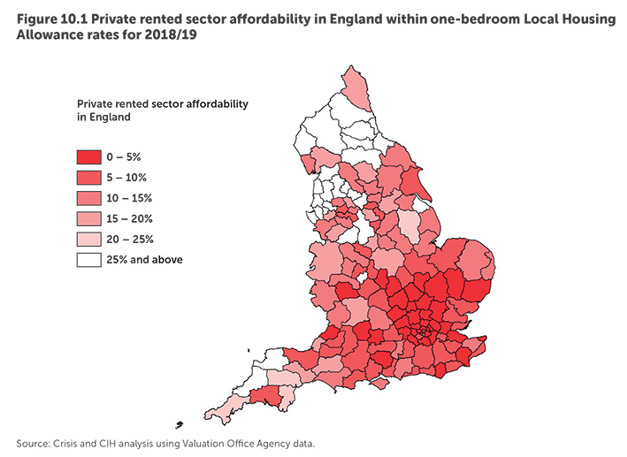

Figure 10.1 shows that in England, London and the South East continue to be the regions where finding housing within Local Housing Allowance rates is hardest. For example, in the most optimistic situation for couples needing a one-bedroom property in London, they would be able to afford seven per cent of the private rented sector in places like Putney or Fulham. And looking in the South East, only 15 per cent of private rented sector properties in Canterbury would be affordable within the rates.

However, similar pressures are also evident in more affordable regions, such as Yorkshire and the Humber. Couples or single people aged 35 and over will find that in three quarters (75%) of areas, less than 18 per cent of the private rented sector will be affordable. Until this year, more than 20 per cent of the private rented sector was affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates in almost all areas in Yorkshire and the Humber. The ongoing effects of the reductions mean this is no longer true.

Overall, for one-bedroom properties, 20 per cent or more of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates in just 29 of 152 areas in England.

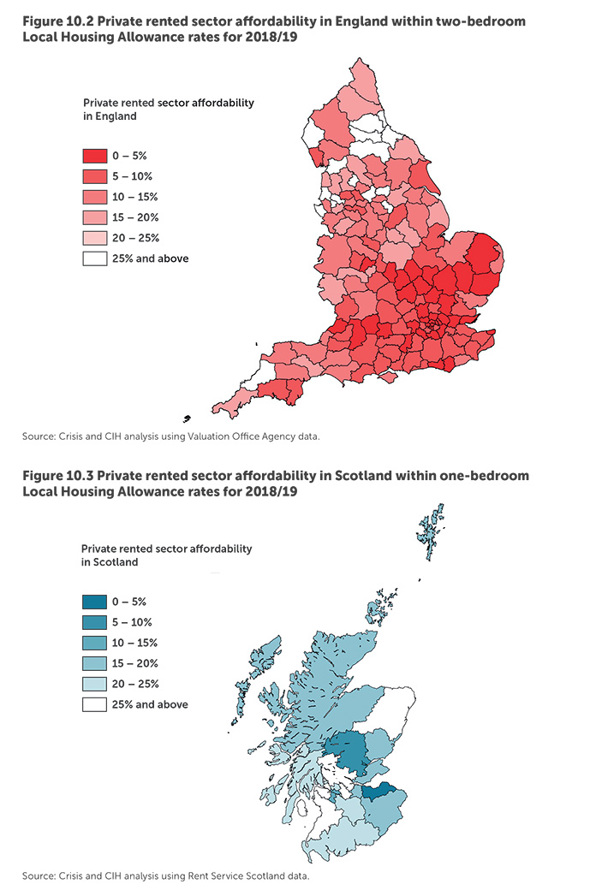

The picture is even more difficult for small families looking to rent two-bedroom properties, as shown in figure 10.2. Twenty per cent or more of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates in just 16 of 152 areas in England.

Of the households considered in this research, small families face the largest gaps between the Local Housing Allowance rate and the 30th percentile of market rents in Britain. They face the largest weekly gap in Central London of £213.60. But high weekly gaps are also experienced outside of London – in Bristol (£39.57), South West Hertfordshire (£38.77) and Bath (£34.14).

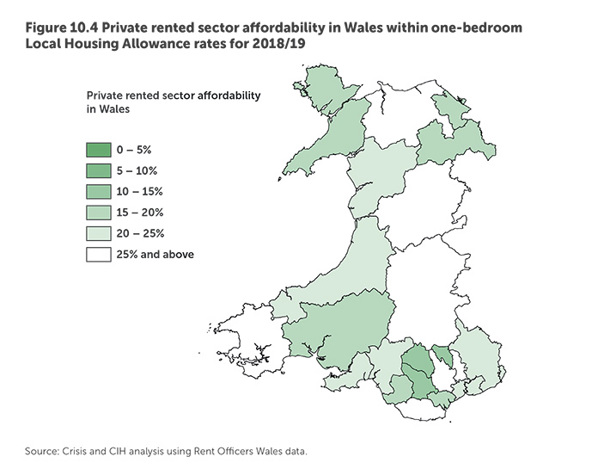

In Scotland, in almost half of areas (eight out of 18), less than 20 per cent of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates for one-bedroom properties. Small families needing two-bedroom properties face the same problem. Figure 10.3 shows that these households will find fewest options in Lothian, Greater Glasgow, and Perth and Kinross.

Households struggle in Lothian in particular. Here, just three per cent of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates for one-bedroom properties, and seven per cent for two-bedroom properties.

In Wales, the picture is more variable. Figure 10.4 shows that there are ‘hotspot’ areas where affordability is a challenge. People needing one-bedroom properties will find affordability a challenge in just under a third of areas (seven out of 22). However, in the same number of areas, more than 25 per cent of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates. In most of Wales, affordability of the private rented sector falls between 20 and 25 per cent.

Affordability also improves for small families in Wales. The Local Housing Allowance rate for two-bedroom accommodation covers at least 25 per cent of the private rented sector in just under half of areas (ten out of 22). However, it is challenging for small families who need accommodation, particularly in Cardiff, Vale of Glamorgan, Ceredigion, and North West Wales. Small families face the largest gaps in Wales in these areas compared to other households considered.

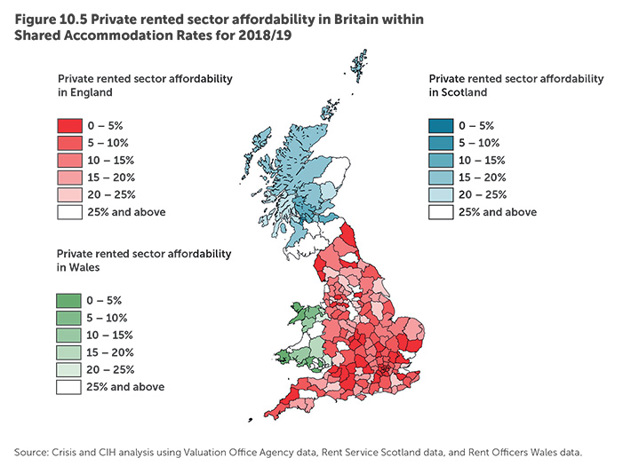

In all three countries, people under 35 who receive the SAR will struggle more to find affordable housing compared to other households.

Figure 10.5 shows the scale of the issue. In England, less than 20 per cent of the private rented sector is affordable within the SAR in 123 of 152 areas (81% of the private rented sector). In Scotland, less than 20 per cent is affordable within the SAR in ten of 18 areas (55%). In Wales, this is true in 11 of 22 areas (50%).

In England, the severity of affordability within the SAR is greater than for one-bedroom and two-bedroom properties. In more than a quarter (27%) of areas, five per cent or less of the private rented sector is affordable. This includes 12 areas where there is no shared accommodation affordable within the SAR. This compares to one area for both one-bedroom and two-bedroom properties where there is no accommodation affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates.

In Scotland, affordability within the SAR is also severe in more areas, such as North Lanarkshire, compared to one-bedroom and two-bedroom properties. In Wales, the SAR is the only rate for which less than ten per cent of the private rented sector is affordable. In Caerphilly and the Vale of Glamorgan, there is no shared accommodation affordable within the SAR.

Gaps in the SAR are likely to be more serious as young people receive lower amounts of overall benefits and so are less likely to be able to make up the gaps from other benefit income. The standard amount of support for non-housing costs in Universal Credit for someone aged under 25 is £251.77 a month, compared to £317.82 for someone over 25. Consequently, even gaps of £5 a week are difficult to manage.

Households in work

Most homeless people (88%) want to work, either now or in the future. Research with formerly homeless people shows that employment is ‘the most important factor in terms of enhancing their quality of life and providing hope for the future.’ Employment can be an effective route out of homelessness. It can help increase financial, and therefore housing, stability.

However, the research shows that when homeless households move into, or are in, employment, they must still manage low budgets because housing costs take up a large proportion of income. Affordability once more becomes an issue and is a barrier to resolving homelessness, or increases the likelihood of repeat homelessness.

This is particularly true in areas where housing is more expensive. Here, households have two options. They can spend less on rent if they can find affordable accommodation, meaning they have more money left over to pay bills, and buy food and clothes. However, affordable accommodation is often linked to poorer conditions and less security in the private rented sector, as discussed in Chapter 11. Alternatively, they can spend more on rent to increase the proportion of properties affordable to them in the private rented sector. But this means they have little left over to cover spending on essentials such as bills and food.

So, even when in work, homeless households are often unable to increase their standard of living to a level where they are at a reduced risk of homelessness. As mentioned, our research with the CIH defines this level as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s Minimum Income Standard.

The research shows that living at the Minimum Income Standard is only possible for single people aged 21 and over that work full time, and couples aged 25 and over where both adults are working. This is due to a combination of higher levels of earnings with age, and lower housing costs for younger people from shared accommodation.

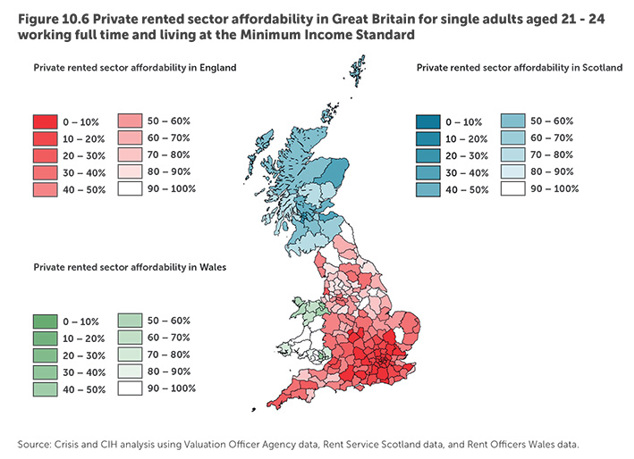

Figure 10.6 shows that for these households, being able to live at a reduced risk of homelessness is more likely in areas where housing is generally more affordable. In England, this means that these households are unlikely to be able to live at a reduced risk of homelessness in London, the South East, the East of England, and in ‘hotspots’ in the South West. In the West Midlands, younger households (aged 21-24) will struggle to secure housing in the private rented sector due to lower National Minimum Wage amounts.

These trends are also seen in Scotland and Wales. Compared to England, rents in these countries are generally lower. This means that on the whole, there is a greater chance for these households to live at a reduced risk of homelessness. However, younger people aged 21-24 will struggle to afford the private rented sector in certain parts of these countries.

In Scotland, they will struggle in Lothian, Aberdeen and Shire, Greater Glasgow, and East Dunbartonshire. In Wales, they will struggle in Flintshire and Caerphilly.

Significantly, most households in the research are unable to reach the Minimum Income Standard and so live at risk of homelessness when in work. This risk is much higher in areas of more expensive housing across Britain.

These households can sometimes live at the UK poverty line in areas where there is more affordable housing. However, poverty is central to homelessness. So even though a household may initially be able to afford the private rented sector, they risk becoming homeless again if the pressure of low incomes and high housing costs becomes too much.

The groups most at risk of homelessness are: young people aged 18-20 due to the lower National Minimum Wage, couples where there is only one earner, and households in work part time. Though this research did not explicitly examine the impact of childcare for small families, it suggests families that have to face childcare costs will also struggle significantly. This means single parents in particular have a high homelessness risk.

In many parts of Britain, the only option for these households is to live off a similar weekly budget as households not in work to increase their ability to rent a suitable and secure home. This leaves them at a high risk of homelessness, despite working.

These findings highlight the importance of the role of employment support for homeless people and people at risk of homelessness. Clearly, the employment opportunities that homeless people aspire to should be tackled alongside affordable housing solutions. These solutions should be both in the private rented sector as set out later in this chapter, and in the social sector, as discussed in Chapter 11. This is crucial to ensuring homeless people and people at risk of homelessness can become financially stable by entering sustainable employment that covers the cost of their housing.

Support from Universal Credit to stabilise housing is vital for people who want to leave homelessness behind. It is also a financial safety net preventing low-income households from becoming homeless in the first place.

To successfully stabilise housing for these groups, investment is needed in Universal Credit to ensure it covers the cost of housing.

In the consultation to inform this plan, people with lived experience of homelessness strongly emphasised the importance of having a benefits system that provides an adequate safety net. This is essential to prevent people from becoming homeless if they experience a period of unemployment or unstable employment. People increasingly felt that the benefits system is no longer providing a sufficient safety net.

“The benefits system doesn’t accurately reflect the real cost of living, it doesn’t cover rent.” (Consultation participant, Croydon)

Problem

The Local Housing Allowance rate reductions have made renting completely unaffordable for homeless people in many areas of Britain. Many households are now in a position where they have few, or no, options to be able to manage the gap between their rent and their Housing Benefit. This means the private rented sector is increasingly unviable as a solution to homelessness. This is particularly concerning in the context of a shortage of affordable housing for low income households across Britain.

Until this year, the reductions meant that affordability of private rents within Local Housing Allowance rates followed a noticeable geographical pattern. The pattern reflected the affordability of rents from when the uprating was first changed from local rents to a flat rate.

It meant that generally, areas characterised by lower rental growth remained affordable, and those characterised by higher rental growth were increasingly unaffordable. The impact meant reductions fell hardest on Housing Benefit recipients living in expensive areas, where demand for housing was also highest.

Consequently, in more expensive areas, households were forced to mitigate the problems caused by significant gaps by moving to areas where housing was more affordable. For example, from 2010 to 2014, there were significant movements of Local Housing Allowance recipients from inner London boroughs to local authorities in the South East and East of England.

This increased the geographical concentration of more disadvantaged households, but also restricted opportunity for households forced to move further from employment opportunities. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) recognised that this movement increased the risk of homelessness for these households.

However, as our research shows, these geographical patterns are diminishing rapidly. In England, there are very few options left in terms of housing market rents within Local Housing Allowance rates. In Scotland and Wales, while options remain, they can be at odds with the amount of housing available.

Households are therefore facing fewer areas where housing is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates. For homeless households, this makes living in the private rented sector extremely difficult. For households at risk of homelessness in the private rented sector, it means they have to find ways to overcome the gaps or face eviction.

Evidence suggests that to date, households have already tried to overcome gaps and avoid eviction. An evaluation of the effects of the first set of reductions to Local Housing Allowance rates, before the freeze, found tenants were forced to cut back on expenditure on household essentials or borrow money from family or friends. Where they were unable to do this, there was a rise in arrears. A 2014 survey of landlords found that 37 per cent had evicted, not renewed or ended tenancies of Local Housing Allowance tenants since April 2011.

The Westminster Government has tried to mitigate the impact of Local Housing Allowance reductions through Targeted Affordability Funding.

Targeted Affordability Funding is a portion of the savings made by the Westminster Government through the changes to uprating since 2014. The funding is used to uplift Local Housing Allowance rates. This is usually by three per cent in areas where less than five per cent of the private rented sector is affordable within Local Housing Allowance rates.

In 2017/18, 30 per cent of the savings from the freeze were used for Targeted Affordability Funding. In the 2017 autumn budget, the Westminster Government increased the portion of savings from the freeze to be used for Targeted Affordability Funding to 50 per cent. This has resulted in Targeted Affordability Funding of an additional £125 million being allocated over two years (2018/19 and 2019/20).

Targeted Affordability Funding allocation is decided by ’ranking all 960 Local Housing Allowance rates in Great Britain according to the private rental market share they can afford in each area according to latest available rent officer data’.

However, the funding has largely failed to address the gaps between Local Housing Allowance rates and market rents, despite the intention to do so.

The higher level of Targeted Affordability Funding for 2018/19 was principally allocated in England. An analysis of the SAR, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom rates for this year shows that 30 per cent of these rates received Targeted Affordability Funding. However, in 74 per cent of areas (103 out of 138) where Targeted Affordability Funding was allocated, five per cent or less of the private rented sector is affordable within the uplifted Local Housing Allowance rate.

This is because allocating Targeted Affordability Funding where the private rented sector is least affordable means it tends to go to areas where rents have been growing fastest. This means it will not completely make up the gaps; it will only reduce the amount of the gap depending on how fast rents grow.

As the reductions in Local Housing Allowance are now at a stage where they are significant in much of Britain, Targeted Affordability Funding is an ineffective solution.

With Local Housing Allowance gaps increasing year on year and creating significant affordability problems in more areas, there is an increased likelihood of evictions and consequently, homelessness. This is particularly true in England, where the ending of an Assured Shorthold Tenancy is the single biggest cause of homelessness. It has already accounted for 78 per cent of the rise in homelessness from 2011 to 2017.

Solution

Returning Local Housing Allowance to the 30th percentile is urgently required to redress homelessness. While this will require significant upfront cost, it will prevent households at risk of homelessness from becoming homeless. It will also support homeless households to resolve their homelessness in the private rented sector.

The affordability research shows that the areas of Britain that offer more affordable housing are characterised by lower rental market growth. This means gaps between current Local Housing Allowance rates and the 30th percentile remain low.

For example, a small family needing to live in a two-bedroom property in East Lancashire in England would find they can afford just 17 per cent of the private rented sector. This is assuming properties are available. Yet an increase of around £1.15 per week would mean the family could afford 30 per cent of the private rented sector.

However, areas where rents are more expensive face large gaps. This makes it difficult for low-income households to find housing in a larger proportion of the private rented sector.

If someone wanted to rent a one-bedroom property in Bath they would find that the Local Housing Allowance rate covers properties in just seven per cent of the private rented sector. To increase the properties available to 30 per cent of the private rented sector means covering a weekly gap of £27.04.

Similarly, looking for a one-bedroom property in Scotland would mean the Local Housing Allowance rate in Lothian covers just three per cent of the private rented sector. An extra £20.22 a week is needed to afford properties at the 30th percentile. Conversely, in Dundee and Angus 19 per cent of the private rented sector would be affordable. Just an extra £1.31 would be needed to look for properties at the 30th percentile.

In more affordable areas, restoring Local Housing Allowance rates to the 30th percentile would not increase levels of benefit entitlement significantly. And so it is unlikely that restoring Local Housing Allowance to the 30th percentile will prompt landlords to increase rents in the bottom third of the market in these areas.

If the Westminster Government uses Targeted Affordability Funding to address concerns with Local Housing Allowance, then at a minimum Targeted Affordability Funding should be better allocated. This means bringing Local Housing Allowance rates back in line with market rents where it is needed most.

To ensure this targets homelessness, the funding should be allocated taking the following into account.

Where Targeted Affordability Funding is most needed, the Local Housing Allowance rate should be lifted to the 30th percentile immediately. This will require funding beyond what is currently allocated until 2019/2020. So the Westminster Government should increase funding for Targeted Affordability Funding to appropriate levels if this approach is taken.

Impact

Increasing the proportion of the private rented sector that can be covered by Housing Benefit is essential. This is both to resolve homelessness and to ensure the private rented sector is a secure option for low-income households. This analysis suggests that on the whole, restoring Local Housing Allowance rates to the 30th percentile would close large gaps between Local Housing Allowance rates and rents in expensive areas. This would make it simpler and more affordable for homeless people to find housing.

The Westminster Government should align all Local Housing Allowance rates to the 30th percentile immediately, allowing for legislative change.

If using Targeted Affordability Funding, then Local Housing Allowance rates should be aligned to the 30th percentile by the end of the freeze in 2020.

Responsibility for change

This approach requires data sharing and the DWP, the Ministry of Housing, Communities, and Local Government (MHCLG), and HM Treasury working closely together. Close working with the Scottish and Welsh Governments, the Valuation Office Agency in England, the Rent Service Scotland, and Rent Officers Wales is also essential.

Problem

The reductions to Local Housing Allowance from the 30th percentile happened through changes to the way Housing Benefit was uprated. If the Westminster Government restores Local Housing Allowance to the 30th percentile, as strongly recommended, this solution must remain sustainable. This can only be achieved by uprating Local Housing Allowance by an appropriate mechanism that reflects how private rents change.

As mentioned, the initial method of uprating was switched from a calculation using local rents to using the Consumer Price Index. This was then limited to a one per cent increase and finally frozen with no uprating altogether. This meant that the reduction from the 30th percentile happened in an unequal way across Britain. This is because real rent increases do not follow this flat rate.

The Consumer Price Index is only very weakly correlated with rent prices. Analysis from the CIH shows that if this had been used to uprate Local Housing Allowance since 2013, the affordability of the private rented sector would be similar to what it is now. This means that if the Consumer Price Index is used for uprating when the freeze on Local Housing Allowance ends in 2020, it will not be enough. Analysis by the Institute of Fiscal Studies has also found that it would result in a further 200,000 people facing a gap between their rent and Housing Benefit entitlement by 2025.

Not only will uprating by the Consumer Price Index see more households facing financial gaps, it will also entrench geographical divergences in affordability across Britain. In areas of high rental growth, rents will rise faster than the Consumer Price Index and reduce the proportion of the market covered by Local Housing Allowance rates. But in areas of little to no rental growth, Local Housing Allowance rates will be inflated as they increase at a level above local rent growth.

This means areas with expensive housing will remain unaffordable for low-income households, whereas those with cheaper housing will become increasingly affordable.

Solution

To retain the link with local rents, the Westminster Government should uprate Local Housing Allowance rates annually in line with projected growth of rents. An average calculated over a maximum of five years is suggested.

Such an approach would create a smoothing effect, so that an average rate balances out annual volatility in local rents.

Impact

Analysis by the CIH suggests that taking an approach based on an average of a measure results in fewer large gaps between market rents and Local Housing Allowance rates. This means over the long term, affordability would not become a particular problem in one area. Their analysis also shows that uprating with a link to actual rent prices is the most effective approach, compared to uprating by the Consumer Price Index which has little relation to rent prices.

Choosing to uprate by a consistent measure should also help provide security to landlords. While rents may outpace Local Housing Allowance rates in a given year, landlords will know how much the Local Housing Allowance rates will be increased by in the next year. This will help with financial planning and management.

Additionally, taking an average of local rents over a number of years will mean the increase is calculated on projected rental growth, rather than past growth. To illustrate, the increase for 2011/12 was based on rental growth over 2010/11. This meant Local Housing Allowance rates inevitably fell behind the 30th percentile in areas of high rental growth. Using projected rental growth will reduce this initial error and make Local Housing Allowance rates more accurate, again providing more security to landlords.

This method for uprating must be implemented by the end of the freeze of Local Housing Allowance rates in 2020 at the latest.

Responsibility for change

The DWP and HM Treasury.

Problem

The method for setting Local Housing Allowance rates has also contributed to some of the gaps experienced by Housing Benefit recipients. Though not restricted to it, this is a problem that is most apparent for the SAR.

Local Housing Allowance rates are based on the entirety of rents that can be collected by rent officers, rather than statistically robust samples. In some areas, the SAR levels have been based on very small samples and are unlikely to reflect the reality of rents for shared accommodation.

In England, the Valuation Office Agency can base its calculations on a limited sample of properties. In 2012/13 the Valuation Office Agency on average based its calculations on the SAR on 102 fewer properties per postcode than advertised on the website spareroom.co.uk. Consequently, it calculated the average weekly rent to be £23.95 lower.

In their 2018 data, the 30th percentile is based on a significantly smaller number of rents compared to last year in some areas. For example, in Bolton and Bury the 30th percentile has been calculated using 39 shared accommodation rents, compared to 205 in 2017. This makes any calculation for 2018 much more volatile than last year, including knowing the accuracy of Local Housing Allowance rates in relation to the market.

This volatility in sampling is due to the fact that rent officers in England, Scotland, and Wales are reliant on landlords voluntarily submitting their rental data to be used. There is no legal obligation in any of the three countries for landlords to submit their rental data to the relevant agencies. This means that Local Housing Allowance rates are based on the capacity of landlords to submit rental data, and their relationship with rent officers. There is currently no way to ensure robust data to track the market, or to use in setting rates.

The impact of this flawed sampling has been reflected in analysis of Local Housing Allowance by the DWP. In 2010, the proportion of SAR cases experiencing gaps was higher than for all recipients, at 67 per cent compared to 49 per cent.

The core concern is that given the SAR is so out of step with rents for shared accommodation, this creates an additional barrier for landlords to let to young Housing Benefit recipients.?Our research confirmed these concerns for young people who need the SAR to afford housing. Across three locations, 13 per cent of advertised properties were affordable with the SAR. When accounting for the proportion of landlords willing to let

to Housing Benefit recipients, just 1.5 per cent (66 of the 4,360 shared properties advertised) were accessible to SAR recipients.

Issues with the volatility of the SAR have been identified in Scotland and Wales where supply issues of shared accommodation, especially in rural areas, are well-known. This method of collecting rates therefore further worsens issues created by a shortage of supply. Overall, the SAR is considered to undermine the ability of Housing Options teams to use the private rented sector to prevent or resolve homelessness.

Solution

For Local Housing Allowance rates to be accurate, landlords should be required to submit annual data on the size of their rental property, and the level of rent they are charging.

This data should be shared with Rent Officers Wales, the Valuation Office Agency in England, and Rent Service Scotland, to support with Local Housing Allowance rate setting. The data could be collected as part of national landlord registration schemes, and require landlords to specify if they rent to Housing Benefit tenants. These already exist in Scotland and Wales, and have been recommended for England in Chapter 11.

Impact

This will increase the volume of data available to set Local Housing Allowance rates. It could potentially mean that there will be high enough volumes of data to be able to set minimum sample sizes for each area for Local Housing Allowance rates, even excluding rents for Housing Benefit tenants. This will improve how robust the data is, and the accuracy of Local Housing Allowance rates.

The data collection would have similar timelines to implementing a national registration scheme in England (see Chapter 11), as it should be incorporated into the design of the scheme. Agencies in Scotland and Wales would need to work to similar timescales to secure data sharing protocols.

Responsibility for change

The MHCLG would be responsible for setting up a landlord registration scheme in England. MHCLG, the Welsh Government and the Scottish Government, need to work respectively with the Valuation Office Agency, Rent Officers Wales, and Rent Service Scotland on data sharing.

Problem

The SAR requires Universal Credit recipients under 35 to live in shared housing. This is often not appropriate for homeless people or those at high risk of becoming homeless.

Concerns about the suitability of sharing as an option have long been raised in relation to the SAR. From 2011 to 2014, there was a 13 per cent drop in single 25-34 year olds claiming Housing Benefit. This is despite the overall number of people claiming Housing Benefit continuing to rise. This drop was particularly significant in central London, where the Housing Benefit caseload fell by 39 per cent.

Landlords and housing advisors interviewed for government research suspected young people were being forced into sofa surfing or rough sleeping after struggling to find shared accommodation within the SAR. In London over this period, there was a 19 per cent increase in the number of rough sleepers aged between 26 and 35.

The Westminster Government has put exemptions in place for some groups that would find shared accommodation difficult, but these are insufficient. The Westminster Government rationale for the SAR is to ‘ensure that Housing Benefit rules reflect the housing expectations of people of a similar age not on benefits’. However, there are some vulnerable groups that are not covered by SAR exemptions, or they may be only covered up to a certain age. This means the current exemptions do not protect young people where it is inappropriate to place expectations of being able to live in shared accommodation.

For example, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness (APPGEH) report into groups at high risk of homelessness found that care leavers have often endured challenging upbringings and trauma. Care leavers told the inquiry they would feel unsafe in a shared home, and that the current exemption up to the age of 22 is not adequate to ease the transition into adulthood.

Similarly, survivors of domestic abuse, who are a group at high risk of homelessness, do not qualify for specific exemptions under the SAR. But it is not appropriate to require these survivors, after fleeing an abusive partner, to share with strangers.

Solution

All homeless people or people at risk of homelessness for whom sharing is not appropriate should be exempt from the SAR.

There are groups that have a high risk of becoming homeless and for whom sharing is likely to be inappropriate.

The current list of SAR exemptions should be expanded to cover people who are homeless or at high risk of homelessness, where sharing is not appropriate.

Through the Keep on Caring Strategy of 2016, the Westminster Government recognised that the exemption to the SAR for care leavers only until the age of 22 may not be sufficient. It stated its intent to review ’the case to extend the exemption to the SAR of housing support within Universal Credit, for care leavers to age 25’.

The Westminster Government should extend the current exemptions to up to the age of 35; when someone is eligible for the SAR. The government should also extend this exemption for the following people.

Impact

Ensuring SAR exemptions are comprehensive is vital. Comprehensiveness means that vulnerable people under the age of 35 for whom sharing is likely to not be a suitable option avoid being at risk of failing to sustain their tenancy. This will help avoid homelessness or repeat homelessness.

The changes to the exemptions should be implemented as soon as possible, allowing for legislative change.

Responsibility for change

The DWP.

For Universal Credit to be an effective tool for responding to, and preventing, homelessness, it needs to function correctly. This was a key theme raised throughout the national consultation undertaken to inform this plan. Below are a number of issues that need to be resolved.

Problem

The roll out of Universal Credit has been beset by administrative errors and delays. Implementation issues have meant vulnerable recipients and people with more complex cases have had to wait more than six weeks for their first payment. Many problems have resulted from administrative errors; existing safeguards applied incorrectly or not set up; and recipients receiving contradictory advice from DWP staff.

This has included homeless people being advised incorrectly about Universal Credit and other benefits. This has created long delays where people are left without crucial financial support. The Trussell Trust, a UK charity that runs a network of foodbanks, has reported that there has been a 30 per cent increase in visitors to foodbanks over six months in areas where Universal Credit has been introduced.

Crisis case study

Local Crisis teams in Brent worked with a client requiring support to manage their housing costs. The client asked for their Housing Benefit to be paid directly to their landlord to make it easier for them. The forms to set up the direct payment were completed, signed and posted with proof of posting. However, the first Universal Credit payment was made in full, including Housing Benefit, to the client’s account, rather than direct to his landlord. This also happened with the second payment.

A Crisis housing coach called the Universal Credit helpline to follow up the issue and was told they had no record of the request for a direct payment to be set up. The housing coach was successful in following this up, recovering all rent owed, and setting up the direct payment again. However, when the direct payment was made, all the payments to the landlord were incorrect. The Crisis housing coach then had to resolve this issue, which took several weeks. The client was safe from eviction due to constant negotiation and communication between the Crisis housing coach and the landlord.

Front-line staff at Crisis report spending lengthy periods repeatedly calling the DWP service centre to understand a payment or query inaccurate payments owed to homeless clients. They report receiving different information from service centres regarding the same issue, and significant difficulties finding DWP staff with sufficient knowledge of Universal Credit.

In some cases, these issues have led to rent arrears for recipients, which have only been resolved with intensive negotiation between Crisis and landlords to avoid eviction. With more complex cases, Universal Credit delays and disputes over payment amounts have taken months to resolve. Homeless people or those at risk often do not have the resources to be able to withstand these significant delays.

Solution

Errors and delays in processing Universal Credit claims must be resolved.

Resources must match demand as the Universal Credit rollout continues. This should include investment in training and numbers of staff in service centres and the helpline.

DWP service centre staff must be properly trained when new changes to Universal Credit are implemented. This includes comprehensive knowledge of safeguards and flexibilities for recipients such as direct payments to landlords and signposting to local authority Housing Options teams in the cases of homelessness or housing instability.

Resources will be required immediately to keep pace with the rollout of Universal Credit.

Impact

This will reduce administrative errors and delays in processing, helping homeless people to get the crucial support they need.

Responsibility for change

The DWP.

Problem

The amount of Universal Credit someone receives can be reduced to pay off money owed to the DWP (known as overpayments from previous benefits), and debts and loans from companies. These are called deductions. Deductions are set up by reducing the standard allowance

of Universal Credit.

For homeless people, and those at risk of homelessness, current deduction rates can leave them in a challenging financial situation. This adds to the pressure on incomes that leads to homelessness and prevents homeless people from resolving their situation.

There is a five-week minimum wait to receive the first Universal Credit payment. However, those with an existing Housing Benefit claim will have their Housing Benefit extended to cover two weeks of the period while waiting for their first Universal Credit payment.

In the 2017 autumn budget, the Westminster Government announced a package of support to ease financial pressures for Universal Credit recipients. This included changes to advance payments, which are an advance of financial support intended for Universal Credit recipients in financial hardship.

Universal Credit recipients can now receive 100 per cent of their monthly payment under an advance payment, which they can pay back over 12 months. The advance can be made available on the same day if the recipient is in urgent need of financial support.

Homeless people and those at risk of homelessness are extremely likely to need an advance payment. This is because they will not have savings to cover their rent and living costs before they are awarded their first Universal Credit payment. This advance payment will then be deducted from their subsequent Universal Credit payments.

There is an overall cap on deductions under Universal Credit at up to 40 per cent of the standard allowance. The cap does not include previous overpayments, and rent arrears or fuel costs may still be deducted beyond the cap.

There are regulations that set the rate of deductions. Currently the rates for deductions are broadly as follows.

Experiential evidence from Crisis local services, the homelessness sector, and organisations such as Citizens Advice, show deductions can be automatically made at unsustainable levels for homeless people and those on low incomes. This is particularly the case where recipients are facing more than one deduction. This is also worsened in cases where mistakes have been made in processing Universal Credit claims.

Citizens Advice case study

‘This winter a client asked for help because she had £30.24 left for the month after paying her rent and bills. When we called the Universal Credit helpline, we found out that there were deductions for rent arrears, water bills, and an advance payment, a DWP overpayment and Council Tax.

It looked like this:

Standard Allowance £317.82

Housing Allowance £395

Deductions £157.58

Total Universal Credit award £555.24

After she has paid her rent (£400), she was left with £155.24. After bills (electricity, gas, TV licence and broadband) she was left with £30.24 for the rest of the month. She was extremely anxious, particularly when we explained that the next few statements were likely to be similar amounts.’

Shelter case studies

Shelter was able to reduce the rent and Council Tax arrears of a client from 40 per cent to ten per cent. However, under Universal Credit, the client’s other non-deferrable deductions increased, so they were still left with deductions of 40 per cent from their Universal Credit payment. As a result, the client was left with just £169 per month to live off.

Another client had deductions of 40 per cent of his standard allowance applied. This was due to fines, housing benefit overpayments, and repayment of an advance payment. He was struggling with anxiety and depression and was waiting for a Work Capability Assessment. He had just £3 for his gas and electricity, and would have to borrow from a friend after that. Shelter issued him with food vouchers because he could not manage on the money he had.

Another client had deductions of 46 per cent applied to his Universal Credit personal allowance. This was for three advance payments, which were wrongly granted, and a social fund payment.

Deductions cannot be made to a Universal Credit claim if the person has a sanction applied (see employment support section). When someone has been sanctioned, they can apply for a hardship loan if they do not have enough money. Since last year, homeless people can access hardship loans immediately if they receive a sanction.

This immediate support is welcome. However, hardship payments are also deducted under the 40 per cent cap from Universal Credit once the sanction no longer applies. Over the long term, it can increase pressure on homeless people and people at risk of homelessness, making it difficult for them to find financial security and stability. This affects whether they can avoid, or resolve, homelessness.

Crisis case study

A client recently began receiving their Universal Credit payment again after a period of sanctions. The sanctions were applied as the client struggled to complete work-related activity due to ongoing health problems. Crisis was supporting him during this time to challenge the sanctions.

The client had to take hardship loans to pay for rent and food while he was sanctioned. Once he began receiving his Universal Credit payment again, the loan was deducted at 40 per cent of his personal standard allowance, leaving him with £140 a month to live off. When a Crisis coach queried this with the Universal Credit helpline, he was told that this amount was correct. This amount left him with little more to live off than when he had been sanctioned.

This pressure on incomes from deductions means homeless people and those at risk of homelessness may not have enough money left over to cover bills, food and any amount they need for rent. The pressure can mean people are forced into higher levels of debt to cover these costs. This only worsens their situation, leaving them further from resolving, or avoiding, homelessness.

Solutions

Homeless people should be able to access the equivalent financial support as an advance Universal Credit payment without having to pay it back.

Advance payments were designed as a solution to the initial wait period in Universal Credit. The welcome changes in the 2017 autumn budget to advance payments do not address the fact that for homeless people, paying back an advance payment is likely to be a struggle. This is especially the case where other deductions are being made to their Universal Credit standard allowance, which is likely. Advance payments, which are necessary for homeless people due to the payment cycles in Universal Credit, add pressure to existing low incomes.

To support homeless people in stabilising their housing situation, they should be given the equivalent of an advance payment award without a requirement to pay it back. This will act as targeted support for those who need it to help with a rapid response to homelessness. It will prevent future financial hardship due to deductions and reduce the risk of repeat homelessness.

The Westminster Government could make this support available through a grant for homeless people. This will support the intention of The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) in England, and homelessness prevention under The Housing (Wales) Act (2014). The grant could be allocated by Housing Options teams working jointly with Jobcentre Plus work coaches (as described in the employment section of this chapter). This will mitigate any concern of creating unintended incentives in the benefits system.

All those identified as homeless or at risk of homelessness should be granted a three-month delay to the start of all their Universal Credit deductions.

DWP guidance states that a three-month delay for deductions for advance payments can be granted ‘in exceptional circumstances’. This delay should be applied to all repayments. Homelessness, or the risk of homelessness, should automatically qualify as an ‘exceptional circumstance’, with the option to ‘opt-out’ should the person wish to.

This delay will allow Jobcentre Plus work coaches to work with recipients and relevant organisations to stabilise housing. It will also give work coaches time to set the most suitable repayment option that does not leave recipients at future risk of repeat homelessness.

Work coaches will also have to support recipients regarding employment. They may help some people move into employment, or increase their working hours within three months. This will improve their financial security and ability to repay deductions.

Deductions must be set at affordable levels for homeless people and those at risk of homelessness to avoid repeat homelessness or homelessness.

This requires the DWP to allow for the option of deductions to be set at a lower rate than they are currently. There should also be an option for a lower overall cap for deductions for people who are homeless or at risk of homelessness.

This cap could be as low as five per cent for a period of time where even low amounts of deductions will increase the risk of homelessness.

In practice, this requires Jobcentre Plus work coaches to be allowed to be flexible. They could use the options of lower deductions rates and a lower overall cap to tailor repayments to someone’s individual circumstances and set an overall cap of all deductions. This would also allow housing associations and landlords to work with DWP to support tenants at risk of homelessness due to deductions.

In a small number of cases, this cap may still not be workable. So, there should also be the flexibility to apply a ‘£1 per debt’ token payment plan, as recommended by debt advice organisations for those with very little available income.

Impact

These changes will ensure homeless people, and those at risk of homelessness, can sustain repayment levels and resolve or prevent homelessness. Creating extra flexibilities, such as an automatic delay to when deductions begin, also enables Jobcentre Plus to support people into work where possible. This will help with setting deductions at a sustainable level.

Implementing these safeguards successfully depends on Jobcentre Plus work coaches recognising and understanding homelessness, and the impact of financial insecurity on housing stability. Recommendations to improve the capacity and ability of work coaches to achieve this way of working are featured in the employment support section of this chapter.

These changes should be rolled out as soon as possible, allowing for legislative change for the provision of grants and to set flexibility in deduction rates.

Responsibility for change

The DWP.

The benefit cap was introduced in 2013. It sets a flat rate amount of benefits that a household can receive. The cap was originally set at the average gross income of a household in work, excluding income from benefits. This was £26,000 a year for couples, with or without children, and single people.

However, a lower cap was introduced that reflected no link to average household earnings. Since 2017, the cap has been £23,000 a year in London for families (£15,410 for single people), and £20,000 across the rest of Britain (£13,400 for single people).

The impact of the lower cap is widespread. In February 2018, 78 per cent of affected households were only capped because of the lower cap levels. Fourteen per cent would have been affected by the previous, higher cap.

The lower cap is different for single people and families, and recognises higher rents in London, but still does not sufficiently take a household’s circumstance into account. For example, the cap is the same amount for a family with two children as for a family with four children.

The cap works by reducing Housing Benefit if the overall amount of benefits a household receives, with some exemptions, exceeds the cap. Under Universal Credit, the cap is applied to the total amount, and not just support with housing costs. Households receiving Working Tax Credits are exempt, to encourage people to consider working enough to be eligible for Working Tax Credit to avoid its impact.

Problem

As discussed earlier in this chapter, people are at an increased risk of homelessness where Local Housing Allowance rates do not reflect market rents. However, if Local Housing Allowance rates are increased to the 30th percentile of the market, as strongly recommended, there will be more households affected by the benefit cap. This issue will also occur when DWP end the freeze on Local Housing Allowance in 2020.

These households, and those already affected by the cap, will simply have less money to spend on other household essentials. They will then experience impossible choices as to whether to pay rent, to pay utility bills, or to feed and clothe their family. Either way, the risk of homelessness increases.

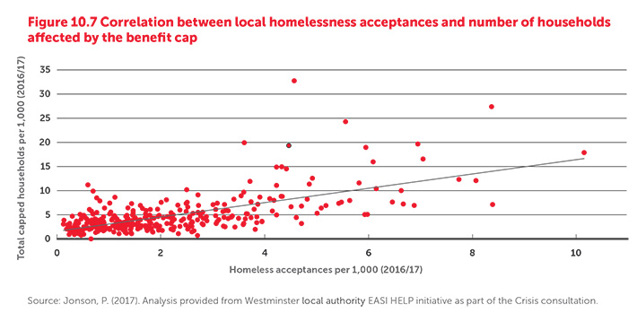

An analysis looking at the rate of homeless acceptances by local authorities and the numbers of households affected by the cap suggest there is a correlation between the two. As shown in figure 10.7, this suggests the benefit cap has an effect on levels of homelessness.

The impact of the benefit cap for affected households is severe. It mostly hits households that are entitled to higher amounts of support in the benefit system. And so it mainly affects households with children.

More than half (56%) of households hit by the cap have lost up to £50 a week from their Housing Benefit, and three in ten (30%) have lost between £50 to £100 a week. For low-income households, this is a significant amount of money that increases their homelessness risk.

This impact of the cap is made worse by the fact that many of the households affected are recognised as experiencing barriers to work. Most of those affected are single parent households. Of these, 77 per cent had at least one child under the age of five, including 33 per cent that had a child under the age of two. Caring duties, along with high childcare costs, are often the main reason why single parents are not in work, or able to increase their working hours, when they have young children. These barriers are recognised elsewhere in the benefit system, where single parents of young children can receive Income Support.

However, for many of these households their only option of avoiding the cap is through work. Moving to cheaper accommodation to avoid the cap is not only impractical for most of those affected, but increasingly impossible. As shown by our research with the CIH, and in Chapter 11, there are too few places across Britain that are affordable to move to.

Shelter case study

Shelter assisted a single mother in Sheffield who faced a £98 a week gap between her Housing Benefit and her rent. Her youngest child was nine months old, but she had been looking for work. She found work as a carer but she had to turn it down because she could not afford the cost of a Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check (commonly known as a background check). She also found it hard to work the hours offered as they clashed with school drop-off and pick up times, and she could not afford the after-school clubs or nursery fees.

The benefit cap therefore increases the risk of poverty and homelessness for families with young children. This undermines strong evidence that action to prevent child homelessness should be prioritised to prevent future homelessness.As well as households receiving Income Support (51% of affected households), 15 per cent were receiving the work-related activity component of Employment and Support Allowance.

People receiving this benefit have been assessed as needing to prepare for work but not actively enter it in the near future, due to ill health and disability. Just 19 per cent of households hit by the benefit cap have been in receipt of Jobseekers Allowance, which requires households to be able to look for work.

Shelter case study

Shelter helped a local authority tenant in Dorset with mental health needs who was hit by the cap when her disability benefits were stopped. She could not move to cheaper accommodation because other types of housing were more expensive. She struggled to pay her rent and was threatened with eviction. To make rent payments, she stopped eating and had lost so much weight that she was down to six stone.

Research by the CIH has shown that households unable to move into work have been forced to go without food, heating or buying clothes for their children, or have been falling into arrears because of the cap. The choice to go without heating or food to avoid falling into rent arrears may decrease the direct risk of homelessness, but should not be a choice a household has to make.

The impact of the benefit cap for those unable to be exempt has been mitigated somewhat by the use of Discretionary Housing Payments (DHPs). The Scotland Act (2016) fully devolved DHPs to the Scottish Government from April 2017, giving it powers to legislate its own scheme.

DHPs are a limited resource that can be allocated, usually for a short period of time, by local authorities if someone experiences a gap between their rent and Housing Benefit. This means there are competing priorities for the funding, as this gap can be caused by a number of welfare policies. In 2015/16, 18 per cent of the DHP budget in Britain was spent on mitigating the impact of the benefit cap.

A number of local authorities have reported that the level of DHP funding has not been proportionate to the rise in demand. The competing priorities for DHP have also meant that some local authorities have attached conditions to the funding in England and Wales. Some local authorities require people receiving DHP to search for work or meet some of the gaps themselves. This effectively leads to a ‘postcode lottery’ regarding allocation. It means in some places DHP cannot help people affected by the benefit cap who cannot move into work to avoid its impact.

In Scotland, the government has committed to using DHP funding to fully mitigate the impact of the Spare Room Subsidy, which has a widespread and severe impact on social housing tenants. The majority of DHP funding is spent on this. If Local Housing Allowance is returned to the 30th percentile, which is strongly recommended, this may affect the funding level needed to ensure the benefit cap does not cause homelessness.

Solution

There must be increased flexibility to lift the benefit cap in specified circumstances related to homelessness.

This flexibility should be focused on people likely to need support from DHPs for a long period of time, for example more than a year, to avoid homelessness because of the cap. The Work and Pensions Select Committee’s inquiry into the cap found that DHPs inadequately support those that are unlikely to be able to mitigate the cap for more than two or three years.

The cap flexibilities should be prioritised for single parents with young children at risk of homelessness, who are recognised as having high barriers to work due to caring duties and high childcare costs. People at risk of homelessness where illness and disability create a barrier to entering work should be included. The flexibilities should also be available for homeless people where the cap is a barrier to securing stable housing.

In practice, this should be implemented through Jobcentre Plus. Housing Options teams and Jobcentre Plus housing and homelessness leads (see employment support section) should be able to lift the cap for the length of time needed. This is to protect households at risk of homelessness that cannot enter work in the near future. In Jobcentre Plus, those affected by the cap and at risk of homelessness should be identified by incorporating housing need in the assessment framework (see employment support section).

The allocation and investment in DHP must also match this flexibility with the benefit cap to prevent homelessness. Investment must be based on both the current impact of the cap and projected impact when Local Housing Allowance is restored to the 30th percentile of market rents.

Impact

This flexibility will mean the cap does not put people at risk of homelessness where they do not have options to avoid the cap, but cannot sustain income levels as a result of the cap.

This flexibility through Jobcentre Plus and Housing Options teams means that those exempt can also be supported towards employment that covers the cost of housing, and childcare where relevant, within an appropriate timeframe. This will help secure and stabilise housing over the long term.

These changes should be implemented as soon as possible, allowing for administrative change. The allocation and level of DHP funding should align with the timescales to return Local Housing Allowance to the 30th percentile.

Responsibility for change

The DWP.

So far this chapter has focused on improving financial support for housing costs. It will now focus on how to help homeless people to find and keep the paid employment that many aspire to.

Homeless people are individuals, not an homogenous group. Employment histories, attempts to find work, and the type of the support needed vary considerably from person to person.Some homeless people are already in work, but struggle to cover high housing costs. Other homeless people are likely to need relatively little support to find work. Yet others need much more help to deal with the barriers to employment affecting them. As well as their homelessness, these barriers can include a lack of skills, training, qualifications, and mental health issues and disabilities.

Some homeless people, such as young people, migrants, and prison leavers, are likely to need more specialist advice and support to increase their chances of successfully finding and sustaining suitable work.

Evaluations of good practice identify key elements of successful employment support as: flexible, person-centred coaching, combined with help that addresses other problems including housing and mental health issues. Working with specialist services, where appropriate, to address these barriers can increase success, as can supporting people in the workplace once they find employment to help them keep and progress in their jobs.

Kings College London research from 2016 found homeless people using employment, training and education programmes, when resettled into housing, were significantly more likely to be involved with these programmes five years on. The study also showed that these programmes were more successful the earlier they were provided to long-term homeless people. Clearly, programmes to support people towards and into work should be provided alongside rapid rehousing models.

Evidence from other programmes for homeless people (for example, the Housing and Employment Programme (HELP) in Westminster) show that assistance with employment goals also improves housing stability itself.

Central to the HELP model is access to on-going one-to-one, flexible and holistic coaching. HELP also gives financial support, including assistance with childcare costs, to reduce additional barriers to work. Within the programme 80 per cent of those it supported remained in employment after 12 months.

Evidence of how to support homeless people into work highlights that employment and housing issues are linked. People struggle to gain employment without housing, and vice versa. This was also strongly evidenced in our research with the CIH, discussed earlier in this chapter, regarding affordability of the private rented sector for working households. So, efforts to help people into employment must understand and respond to housing needs if they are to be successful.

Too often this link is not made when homeless people seek assistance from Jobcentre Plus.

Our recommendations for reform involve the following interconnected issues.

Problem

Jobcentre Plus is often the first port of call for homeless people and those at risk of homelessness who need support from the welfare system. Work coaches in Jobcentre Plus can apply safeguards through Universal Credit to support homeless people to stabilise housing. These safeguards should also protect people at risk of homelessness from further housing instability.

This includes setting up direct payment of Housing Benefit to landlords where necessary or applying the homeless easement to job searching. The easement applies to newly homeless people and enables them to have a period where their job-seeking requirements are suspended, so that they can focus on stabilising their housing.

Another form of help that should be available for Universal Credit claimants affected by homelessness is the Flexible Support Fund. This fund should provide financial support to reduce barriers to work for those on low incomes.

A number of issues with the Flexible Support Fund have been raised since its creation. These include:

This has been reflected in the fact that the fund has been underspent. In 2014/15, almost half (48.8 per cent) of the available budget under the Flexible Support Fund was not spent, and in 2015/16, the underspend was 24 per cent.

This reduction in underspend appears to be from a reduction in the money available under the Flexible Support Fund. It has not resulted from addressing the on-going concerns about the lack of awareness of the fund within Jobcentre Plus and how to use it. To offer the right support for homeless people and those at risk of homelessness, Jobcentre Plus staff must genuinely understand homelessness and housing need. The detrimental impact that homelessness has on someone’s health and their realistic ability to pursue employment goals should be understood.

In many circumstances, people will not necessarily have accessed local authority statutory homelessness provision. Even where they have, this information may not currently be considered as part of the assessment process at Jobcentre Plus. In England, this situation should improve from October 2018 with the implementation of the duty to refer under The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017). From this date, Jobcentre Plus must refer consenting customers identified as homeless to local authority Housing Options teams.

The experience of local Crisis teams of working closely with Jobcentre Plus has shown that staff can struggle to recognise, understand and respond to homelessness. This was also highlighted as a key issue by people with experience of homelessness participating in the consultation to inform this plan.

Work coaches are required to apply time limits when working with Universal Credit claimants. Initial interviews for new claims last 40 minutes; on-going appointments are limited to ten minute time slots. This partly explains the difficulties work coaches face in identifying the details and complexities of homelessness cases, and helping people faced with both unemployment and housing crises.

Jobcentre Plus staff need a good working knowledge of homelessness itself, particularly how a lack of stable housing can affect someone’s ability to find work.

Crisis’ clients and staff report that without this knowledge work coaches unintentionally create barriers for homeless people to stabilise their housing. This can also make it harder for them to focus on work. For example, work coaches do not apply the homeless easement in Universal Credit, which would allow homeless people to prioritise finding stable accommodation, before searching for work. Crisis services report that where this has been applied correctly, it has been hugely beneficial for homeless people and has allowed them to sustainably work towards employment goals.

Understanding the interaction of housing and employment means Jobcentre Plus staff can make employment requirements and outcomes more realistic to homeless people.

In Edinburgh, initial training given by Crisis team members to Jobcentre Plus work coaches has resulted in the two organisations working as partners. This is supported and led by a homelessness lead in the Jobcentre, and includes fortnightly drop-in sessions where Crisis coaches spend allocated time at Jobcentre Plus. This means the Jobcentre Plus work coaches can make appointments for their customers that have housing and homelessness issues with the Crisis coaches. Crisis and Jobcentre Plus work coaches work together to ensure the support provided complements each other.

In Newcastle, Crisis teams are involved in a Homelessness Prevention Trailblazer Programme. This pilot project is testing new ways of working with Jobcentre Plus and the local authority to prevent homelessness under The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) in England. Newcastle City local authority, Newcastle Jobcentre Plus, Crisis, and Your Homes Newcastle have built partnership working towards agreed homelessness prevention goals.

Findings from the first six months of the pilot are positive. Most people engaged in the programme are benefiting from either having their housing stabilised or their homelessness prevented. And some have been supported to find work.

Crisis case study

Kristina* had previous experience working as a driver, but was claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance after a long period out of work. She was supported by Jobcentre Plus to obtain professional driving qualifications and to update her CV. She lacked confidence and was very anxious, requiring more intensive support than her Jobcentre Plus work coach was able to offer. She was living in an overcrowded house with eight other people, occasionally sleeping on a friend’s kitchen floor. Kristina did not see herself as homeless and was afraid of mentioning her housing situation

to Jobcentre Plus.

When she heard about Crisis in London through her local church group she approached them for help. Crisis provided intensive coaching support, training on how to speak to employers and support to create an email account with a member of staff present. She volunteered as a mini bus driver over Christmas and the following month started work as a minibus driver for a local community transport service. She now works as a school bus driver and is looking for work as a London bus driver.

Crisis case study: Newcastle Homelessness Prevention Trailblazer

Ben* came to the Jobcentre Plus explaining he was sofa surfing with friends. He was extremely anxious and depressed as he was no longer able to continue this arrangement, and had nowhere else to stay. This meant he was at risk of rough sleeping. Through the Trailblazer Programme, Jobcentre Plus had close links with Crisis and so Ben was referred to Crisis teams in Newcastle for support with housing and his mental health needs.

The Jobcentre Plus work coach immediately applied the homeless easement to Ben’s Universal Credit claim. This allowed him to focus on stabilising his housing. Crisis secured stable housing within three days and set Ben up with Crisis progression and wellbeing coaches. Ben’s easements were continued while he used other Crisis services. This included taking the Renting Ready qualification to manage his own tenancy.

Given Ben’s progress, his Jobcentre Plus work coach asked him to consider volunteer work as part of his commitments. So, he successfully volunteered in a senior position which involved fundraising for a local event.

Crisis and Ben’s work coach in Jobcentre Plus are working closely together supporting Ben to complete an employment trial in hospitality.

*Crisis clients, not their real names.

Solution

Establish a network of housing and homelessness leads in Jobcentre Plus to integrate housing and employment support.