This chapter sets out how to achieve the fourth and fifth definitions of ‘homelessness ended’ as described in Chapter 3 ‘Defining homelessness ended’.

Definition 4 relates to successful homeless prevention for people who have been the responsibility of the state. This includes: previously looked after children (care leavers); people released from prison; people leaving the armed forces, and people discharged from NHS care. It also includes people who have been the responsibility of the Home Office through the asylum and immigration system.

Importantly, this definition is about the point of transition when leaving state institutions/care. It is not about preventing the prospect of future homelessness for all those who have ever been in care, prison, etc.

Transition is the opportunity for successful prevention. There is solid evidence that these opportunities are consistently missed, leading to people leaving state institutions being overrepresented in the homeless population.

But although definition 4 is about a transition, prevention of homelessness should start much earlier – before the person’s actual transition, or departure from an institution. Because exit dates from institutions such as prison are often known many months or even years in advance, arranging appropriate housing arrangements before release can be done much earlier.

Definition 5 relates to preventing homelessness for those at immediate risk of it. ‘Immediate’ refers to an assessment that homelessness is likely to occur in the next 56 days. This reflects the current statutory framework in Wales and England. In these countries, local authorities have a duty to take reasonable steps to help prevent homelessness up to 56 days before it happens. As detailed later in this chapter, we strongly recommend that Scotland adopt a similar duty.

Combined, these definitions present a targeted approach. They support those groups identified as at an acute risk of homelessness, and those people who need immediate action to stop it happening. There is likely to be some crossover between the two groups.

Prevention can be seen as a continuum of action depending on how ‘early’ the intervention occurs in the predicted likelihood of a problem.

It is useful to see the definitions adopted for this plan within the framework set out in studies on homelessness prevention, which reflects a wider agenda for ‘early action’ in public services.

The strategies recommended in this chapter fall within the secondary prevention category. Through this focus we are not diminishing the importance of primary measures in a broader context to address links to homelessness. Addressing homelessness is not a replacement for action to reverse rates of poverty, inter-generational deprivation, and other issues that affect the broader risks of homelessness over time.

To gather evidence of successful interventions and policy changes in preventing homelessness, we researched the extensive literature already in place and commissioned research where necessary, this included the following:

The standard of evidence about how to prevent homelessness varies. We know that homelessness has been successfully prevented for different groups (for example, for armed forces veterans in the late 1990s and early 2000s). However, there is an urgent need to improve data collection and outcome measurement in this area. Despite the lack of strong evidence there are good-practice examples and we indicate these in this chapter wherever possible.

The human cost of homelessness is at its highest when it is continual or is recurrent. Repeated and long-term exposure to homelessness damages physical and mental health. It also seriously affects the financial and social prospects of people and their families.

The financial cost and cost savings of effective prevention are also important. In the US and parts of Europe, the patterns of service use by homeless people have been explored by merging large-scale administrative datasets.

This research found that higher rates of service use – medical, mental health or criminal justice – are associated with long-term and repeat homelessness. By looking at the way homeless people use services, the research identified the high financial costs of long-term and repeat homelessness.

A recent study, which interviewed 86 people, who had been homeless for at least 90 days, concluded public spending would fall by £370 million if 40,000 people were prevented from experiencing one year of homelessness. The savings echo similar findings in both the US and Australia.

The economic case for intervening earlier to prevent the suffering of homeless people was brought to public attention in the US in 2006, in The New Yorker magazine. It featured the tragic life and death of Murray Barr, or ‘Million Dollar Murray’.

Murray Barr, from Reno, Nevada was a well-known homeless man, famed locally for his alcoholism and outrageous behaviour. Over the ten years he was street homeless in Reno, Murray Barr was repeatedly arrested and admitted to hospital. However, he was always released back to the street rather than into housing.

Following his death, local police officers calculated Murray’s cost to local public services, including hospital care and short-term abstinence programmes. They concluded: ‘It cost us one million dollars not to do something about Murray’.

’We are absolutely changing the focus of the way that we deal with homelessness in Wales, rather than an element of dealing with homelessness at a reactive stage. We are looking at a preventative model and are working through with people, at a very early stage, the duties of local authorities to deal with homelessness.’ Carl Sargeant AM, Introduction of the Housing (Wales) Bill, 19 Nov 2013.14

‘I know that the bill cannot do everything. It will not tackle issues relating to supply, and it will not be a magic bullet to clear the streets of homeless people overnight. What it will do, however, is introduce a longterm cultural change which will, over time, bring about a different way of working among local authorities that will stop people from getting into the terrible position of being homeless in the first place.’ Bob Blackman MP, The Homelessness Reduction Bill, Second Reading, 28 Oct 2016.

There is a strong political consensus across England, Scotland and Wales on the need to fund and to promote measures that prevent homelessness. This dates back to The Housing (Homeless Persons) Act (1977), which gave duties to local authorities to assist people under imminent threat of homelessness (albeit only for those classed as ‘priority need’).

Across Great Britain, each nation is now at a different stage of adopting formal and legally enforced approaches to homelessness prevention, as detailed below.

Outside the statutory homelessness system, we also have a number of key assets that assist homelessness prevention. People at risk of homelessness can access state support with housing costs, and use public services without charge, including the NHS and social care. In an international context, these are big advantages in the fight to prevent and end homelessness.

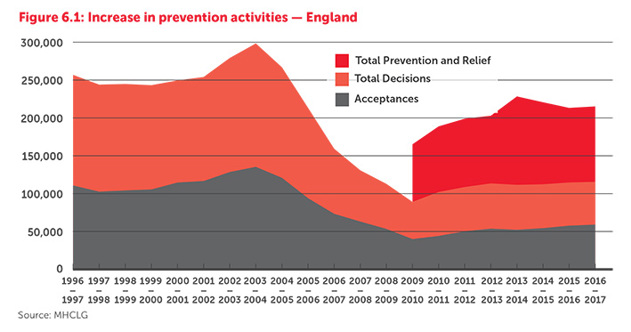

In England, the prevention agenda was expanded in 2002/3 when the government introduced a legal duty for local authorities to produce homelessness prevention strategies.16 This was alongside the formal introduction of the Housing Options approach. The introduction of preventative strategies was set against the backdrop of rapidly rising acceptances of statutory homelessness applications.

Housing Options is a catchall description. It encompasses the ways a local authority can strive to prevent homelessness, and the need for a household to be rehoused under the ‘full’ homelessness duty to provide an off er of new settled accommodation. Typically, this involves a personalised plan, either to keep a household in their existing home, or to quickly access alternative accommodation, often in the private rented sector.

This approach has been lauded as a culture shift that means ‘a proactive rather than reactive style, with an increased emphasis on networking, negotiation and creativity’. However, Housing Options critics have pointed to the freedom local authorities have to stop (or ‘gate-keep’) homeless households from making an application for assistance,and from accessing their entitlements to rehousing once homeless. This is seen as a particular risk when authorities have access to a limited stock of social housing and a prohibitively expensive private rented sector.

A decade after Housing Options was introduced in England, concerns developed regarding funding cuts affecting some local authorities’ abilities to deliver a successful Housing Options service. Additionally homelessness prevention sat outside the statutory framework. This left local authorities exposed to legal challenge when providing preventative services as opposed to access to the full duty to rehouse people.

In 2014 we published our No One Turned Away report. It documented the experiences of ‘mystery shoppers’ presenting cases of homelessness and significant vulnerabilities in 87 local authority visits across England. This report highlighted good practice in some local authority areas, but also systematic ‘gatekeeping’ in others, where people were denied the chance to explain their needs and to access services.

In 2015, we assembled a panel of experts to consider options for legal reform in England. This group was drawn from leading homelessness charities, academia, local authorities, housing specialists and legal experts. Leading academic expert, Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick, chaired the group. Over six months, the group considered recommendations for reform that would increase entitlements for single homeless people, and protect duties owed to priority households (typically families with dependent children).

In February 2016, the panel produced a set of proposals that owed much to the emerging example in Wales. They focused heavily on the benefits of both homelessness prevention, and of removing eligibility barriers for homeless households. These proposals were crafted into a potential parliamentary bill to demonstrate to MPs the necessary legal steps for achieving the aims of the panel report.

Later in 2016, Conservative backbench MP Bob Blackman was drawn in the private members’ ballot for the parliamentary session, and chose to adopt the reforms set out by the panel. Mr Blackman’s proposals became the Homelessness Reduction Bill, for which he gained cross-party and government support. The bill received royal assent in April 2017. The majority of the duties contained in the Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) came into force in April 2018.

Local authorities in England are broadly in favour of the purpose of these reforms. However, they have expressed concern about the availability of funding and accessible housing stock to enable them to successfully discharge their new duties. The government has allocated councils £72.7 million to local authorities. But estimates from London Councils claim that the new duties will cost London boroughs alone £77 million per year.

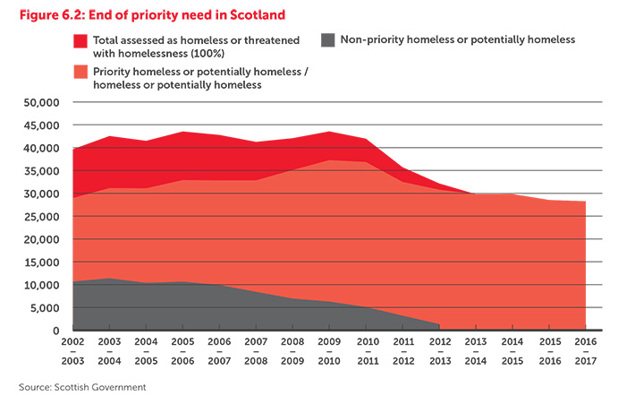

As detailed in Chapter 2 ‘Public policy and homelessness’, homelessness reform in Scotland, following devolution of powers in 1997, focused on abolishing priority need. This followed the passage of The Homelessness etc. (Scotland) Act (2003). Alongside this major reform, effective in 2012, the Scottish Government made significant investments in homelessness prevention (see figure 6.2).

In 2010 the government introduced Housing Options, providing investment of just under £1 million. It established five Housing Options Hubs to share best practice and practical assistance on a regional basis. The Scottish Housing Options is described as:

’A process which starts with housing advice when someone approaches a local authority with a housing problem. This means looking at an individual’s options and choices in the widest sense. This approach features early intervention and explores all possible tenure options, including council housing, Registered Social Landlords and the private rented sector. The advice can also cover personal circumstances which may not necessarily be housing related, such as debt advice, mediation and mental health issues.’

As in England, the introduction of Housing Options had an immediate and dramatic impact on the statutory homelessness system. Applications fell by 19 per cent in 2011/12, and then by a further 13 per cent in 2012/13. Acceptances have reduced by 23 per cent since 2010/11.

The principle of homelessness prevention through Housing Options has widespread support in Scotland, but there are serious concerns about its practical application. In 2014 the Scottish Housing Regulator published a review of Housing Options,28 which reported:

‘Staff in some councils are working to targets for the reduction of homelessness applications as a performance measure for Housing Options. The use of reductions in numbers of homeless applications as a solitary measure of the success of Housing Options can introduce the risk of organisational behaviours that act against the achievement of good outcomes for people in need. We saw a number of examples where local authorities had targets in place and where people who were homeless were not being provided with appropriate advice and assistance in accordance with the homeless legislation.’

This reflects a regularly reported concern about the prevalence of gate-keeping practices. There is also a concern that official homelessness acceptances and prevention statistics reflect a mixture of good practice and outcomes for households, and some poor practice diverting people from help.

These concerns, and recent successes in Wales in extending homelessness prevention duties to local authorities, have led to calls in Scotland to extend the statutory homelessness system to include preventative approaches. This is something that the Scottish Government is currently considering, and is wholly endorsed by Crisis.

Until 2014, Wales had the least developed homelessness prevention approach of the three nations. It had not adopted Housing Options in the same way as Scotland or England.

Following the advent of primary law making powers for the Welsh Government in 2011, the priority of tackling homelessness through improved legislation soon emerged. Dr Peter Mackie from Cardiff University was commissioned by the Welsh Government to review homelessness legislation, and to make proposals for improvements.

The Mackie Review sought to address two key weaknesses in the existing system. First, there was a growing inconsistency in preventative Housing Options approaches, which sat outside the statutory framework. Second, that often no ‘meaningful assistance’ was given to non-priority homeless people, especially single men. In response, Mackie proposed a ‘housing solutions’ model. This model would switch the emphasis of local authorities to preventative and flexible interventions, aimed at resolving homelessness before the main rehousing duty was necessary.

The proposed new approach would entail a duty on local authorities to ‘take all reasonable steps to achieve a suitable housing solution for all households which are homeless or threatened with homelessness’. Mackie suggested extending the period when someone could be deemed to be threatened with homelessness from 28 to 56 days. He also said the prevention duty should be owed to all applicants, regardless of priority need, local connection or intentionality.

These recommendations were adopted by the Welsh Government in The Housing (Wales) Act (2014). More widely, homelessness prevention alongside other elements of early intervention have become part of the Welsh Governments Future Generations Strategy.

These reforms have been largely welcomed in Wales,36 particularly because they have increased the number of people that can be helped, and have increased the flexibility of local authority services. The headline statistics report a 69 per cent reduction in homelessness acceptances between 2014/15 and 2015/16. For people threatened with homelessness, 65 per cent had their homelessness successfully prevented in 2015/16.

The SCIE study into ‘what works’ to tackle homelessness, looked at the evidence base for prevention services. This included services for people at immediate risk, and also those to prevent homelessness for people leaving state institutions. The final part of this section also looks at the evidence base for the prevention of youth homelessness.

The SCIE study found that successful prevention services for people at immediate risk of homelessness have the following core elements.

Housing Options is not, strictly speaking, an evidence-based programme, but it contains all elements identified as successful from the international evidence. Personalised and flexible case management, alongside provision of expert advice and financial assistance, are all elements of a good Housing Options service.

While there is an on-going need for improved data collection and sufficient funding for Housing Options, it is also very positive that all three nations have adopted the model. This is reinforced by the analysis from Heriot-Watt University, which found that ‘maximal prevention’ through a Housing Options approach is an impactful measure in lowering projected levels of homelessness.

The common core elements of successful Housing Options approaches have been identified as follows.

These solutions were highlighted throughout the consultation undertaken to inform this plan as important elements of a successful homelessness prevention approach.

A successful Housing Options approach will operate to a 56-day timescale. It will use a personalised housing plan to set out the actions that the local housing authority and the household at risk of homelessness should take to prevent them from becoming homeless. As is already the case in England and Wales, this should be provided within the statutory framework.

The SCIE study identified some common barriers to successful prevention through a Housing Options approach. Limited access to affordable housing, either temporarily or as settled rehousing, is of course the major concern. So the potential of Housing Options approaches will rely heavily on overcoming these problems for homeless households.

Chapter 11 ‘Housing solutions’ outlines the reforms necessary to meet the housing requirements of homeless households. Chapter 10 ‘Making welfare work’ sets out the changes to Local Housing Allowance rates needed to ensure this housing is affordable.

The baseline success rates of statutory prevention services (via local authority Housing Options) are drawn from data in Wales. In 2016/17, almost two thirds (62%) of households assessed as ‘threatened with homelessness’ (5,718 of 9,210) had their homelessness successfully prevented. A two-thirds success rate is reasonable to assume for households at immediate risk of homelessness. This is providing there is a consistent statutory duty for prevention across Britain with sufficient local authority funding, and that housing supply and welfare barriers are addressed.

The most successful approaches to prevention are those that start as early as possible to identify people at risk of homelessness. It should not be left to local authority housing teams to start prevention work when people are at immediate risk (56 days). Those leaving institutions could have been assisted much earlier. Services within prisons, hospitals, asylum support services, local authority leaving care teams, and armed forces discharge teams must see homelessness prevention as a core part of their work.

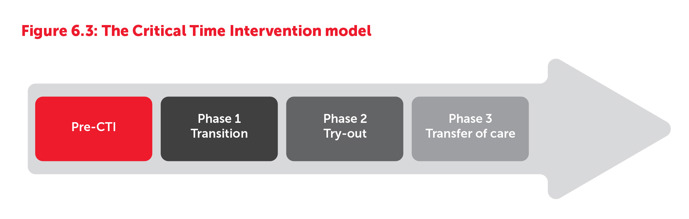

CTI has worked across a variety of groups of people leaving state institutions. The evidence regarding its success is largely drawn from outside the UK, but reflects many elements of good practice seen in resettlement and move-on arrangements in this country.

CTI is a time-limited evidence based practice that supports people vulnerable to homelessness during periods of transition. CTI has been applied with armed forces veterans, people with mental illness, people leaving prison, and many other groups. It is a housing-led approach providing rapid access to housing. It also features an intensive case management approach to address the particular needs of people once they have security of accommodation.

The CTI model (figure 6.3 above) is based on moving through clear, time-limited phases that are agreed and appropriate for the programme of support. A case manager will start to build a relationship while the individual is still in the institution, for example prison or hospital (or even emergency housing). At the point of transition into the community there are three distinct phases that are followed:

Emotional support is often also important, applying psychologically informed techniques to help someone stay motivated, and to avoid isolation. The case manager will often also act as a negotiator or mediator with neighbours, or with a landlord, helping to overcome any conflicts during the transition.

This period allows the case manager to assess how the person is settling into their accommodation and local community. Careful attention is paid to helping them access mainstream support services, such as drug and alcohol treatment and regular health appointments.

CTI has been widely adopted in the US, and in various European contexts. In Denmark the success rate for service users who ‘have been housed and maintained housing’ is 95 per cent.

It is an empirically proven model, and the SCIE study identified a number of contexts and groups of people leaving institutions for whom tenancy sustainment is significantly increased through CTI. These included armed forces veterans, patients being discharged from hospital, young people, and prison leavers. Homeless Link in England has reported that CTI as a targeted approach ‘could arguably be transferred to any vulnerable group’.

In a domestic setting CTI is not dissimilar from many good models of resettlement and tenancy sustainment practice. Factors that the SCIE study identified as critical to the success of CTI delivery, included consistent face-to face contact with a case manager, and the security of housing offered.

Young people leaving care are at high risk of homelessness and often have associated problems relating to mental health, drug and alcohol abuse, criminality and employment. One-third of care leavers experience homelessness in the first two years after leaving care.

Care leavers are entitled to statutory homelessness support and to various on-going support arrangements from their local authorities. However, they also regularly report falling foul of systemic barriers such as ‘intentional homelessness’ or restrictions in accessing benefits. In Scotland, more specific concern has been raised about care leavers spending too long living in unsuitable temporary accommodation.

Evidence of what works to prevent young people exiting the care system into homelessness is relatively weak, given the regularity and prevalence of the problem. There is an urgent need to invest in evidence-based solutions, though good practical guidance is available.

Barnardo’s and homelessness charity St Basil’s have produced specialist guidance – an invaluable resource – for local authorities and housing providers working with care leavers at risk of homelessness. It details a number of best practice examples, and provides a framework for improvements in local areas. The framework is based on some key principles, stating that young people leaving care are:

The guide provides practical tips for avoiding homelessness among care leavers. It helps young people: successfully navigate Housing Options; choose accommodation before leaving care; manage any housing crisis that does occur, through use of short-term accommodation; arrange tailored support when in accommodation, and choose a longer term housing solution.

The corresponding guidance for Wales has been produced and published by Barnardo’s Cymru and Shelter Cymru.

Ex-off enders leaving prison often struggle to access accommodation either before, or after their release. This is not only because of difficulties getting new housing upon release, but also because people who had accommodation before their arrest can lose it while in custody.

Fifteen per cent of newly sentenced prisoners report being homeless before entering custody. Of the approximate 66,000 prison leavers a year (England and Wales only) it is unclear how many experience homelessness upon release. However, the Prison Reform Trust reports that six in ten female prisoners have no home to go to upon release. And in 2002 the Social Exclusion Unit reported that a third of prisoners lose their home while in prison. Latest figures for Scotland show that six per cent of homeless applicants (1,921 people in 2016/17) became homeless straight from leaving prison.

Aside from CTI, there is no single evidence-based programme for the prevention of homelessness for prison leavers, although of course much good practice exists.

Housing-led solutions, coupled with specialist advice and preparation before release are solid principles of success. A good Housing Options approach will include this and will involve going in to prisons to prevent homelessness for people long before their release.

The St Giles Trust, a charity helping people facing severe disadvantage, operates a scheme to provide peer mentors in prison and community settings. The scheme provides tailored specialist advice and has shown strong success in improving access to and sustainment of housing.

In Scotland, the Scottish Prison Service has produced the Sustainable Housing on Release for Everyone (SHORE) standards. The SHORE standards are a multi-agency approach. They are specifically designed to ensure that ‘people leaving prison can access services and accommodation in the same way as people living in the community.’ There is strong evidence that Housing First and CTI approaches not only resolve homelessness in the vast majority of cases, but also successfully reduce reoffending rates. We strongly recommend that these housing led approaches, including the key elements of the Housing Options approach described above, are scaled up across Great Britain to prevent homelessness for prison leavers.

As detailed in Chapter 2, the reduction in homelessness among armed forces veterans is a good example of public policy success. Data suggests that between 1994 and 2008 the percentage of homeless people from the armed forces has dropped from 25 per cent to six per cent. More recent data from 2014, taken from a large sample of single homeless people across Great Britain, shows that this has reduced to three per cent.

The reduction in veteran homelessness is a good example of responses to homelessness being co-ordinated across government departments, and not simply requiring local authorities to take responsibility. Veterans deemed vulnerable through leaving the armed forces became a ‘priority need’ group under homelessness legislation in 2002. At this time the Ministry of Defence also expanded its own ‘pre-discharge resettlement service’. This service requires those at risk of homelessness (and other vulnerabilities) to be assessed and for housing advice to be provided to people before leaving the armed forces.

Despite such success there is a frustrating lack of evidence about how the reductions in veteran homelessness have been achieved. There are clearly good services and approaches to the issue but a lack of data about them. The SCIE study again identifi ed CTI as an eff ective model for this group, referencing data from the US.

The Home Offi ce is responsible for supporting people while their asylum claims are processed, including providing housing. Asylum seekers are, by virtue of their circumstances, at a high risk of destitution and homelessness.

The transition from asylum support accommodation has become a cliff-edge of homelessness. Like the prison system or hospital discharge, the state withdraws responsibility and assistance at an arbitrary point. This is regardless of whether alternative accommodation has been secured or homelessness prevented.

If asylum seekers are given a positive decision on their application, newly recognised refugees have 28 days before their support is cut off and they are forced to leave their accommodation. Twenty-eight days is too short and does not give people the time they need to access financial support and housing.

This is exacerbated by the delays many people experience in receiving the documents they need to register for welfare support, open a bank account and access housing. The lack of support they experience is in stark contrast to the support provided to refugees who come to the UK through one of the government-led resettlement schemes. They are provided with accommodation and receive support to access services and find employment.

Chapter 14 ‘Homelessness data’, describes the data available about the nature and extent of the problem. Very little published data is available. Although in London we know that 2.6 per cent of rough sleepers, 74 people at the last count, reported that their last settled base was asylum support accommodation.

There are examples available of schemes to host and support migrant homeless people, but there are no evidence-based interventions to reference for this group.

‘Homeless people in the UK don’t die from exposure. They die from treatable medical conditions.’ Dr Nigel Hewitt, Medical Director, Pathway

Effective homelessness prevention within NHS care is both an opportunity to deal with housing issues and with medical conditions. There are a range of such opportunities regularly associated with hospital discharge, from short-term accident and emergency care, through to longer term psychiatric care admissions.

Homeless Link reported in 2014 that more than 36 per cent of homeless people were discharged from hospital onto the street, without underlying health problems or housing being addressed. This is corroborated by reports from NHS staff that they have little understanding of how to deal with the housing needs of homeless patients. As with prison, homelessness can also occur while people are detained/admitted; this also presents an opportunity for immediate action.

In November 2017 The Lancet published a major review of what works to prevent and relieve homelessness and provide effective treatment for homeless people. The review points to the success of case management approaches such as CTI:

‘In homeless populations, case management was associated with improvements in mental health symptoms and substance use disorders compared with usual care. Case management with assertive community treatment (multidisciplinary team with low caseloads, community-based services, and 24hr coverage) reduced homelessness, with a greater improvement in psychiatric symptoms compared with standard case management for the treatment of homeless people with severe mental illness’.

Once again this points towards the need for tailored and intensive case management, but this time in a health setting. This kind of intervention has much in common with the Pathway model, which has been developed in English hospital settings. It involves a specialist case management approach that includes medical interventions alongside housing and other advice.

The Lancet review echoes the findings of the evidence assessment in the SCIE study, in also pointing to the strong evidence base for housing-led solutions.

A review of homelessness prevention in health settings from Homeless Link also highlights the success of housing-led approaches. It points to the success of immediate rehousing alongside financial assistance and ongoing support. This has been shown to be particularly successful for planned discharge from psychiatric units. The same study once again points to the success of CTI for this group.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has also published useful guidance on improving the transitions for people with social care needs (including homeless people) leaving hospital.

As with agencies responsible for the groups above, the NHS in each nation must assume responsibility for homelessness prevention to achieve successful transition and discharge. Time and again the evidence of what works includes active discharge planning within the health system. While this might require rapid access to settled accommodation, it cannot be left to housing agencies and local authorities who themselves cannot plan and deliver a successful exit from healthcare.

In Scotland, statutory guidance for Health and Social Care Integration Authorities was published in 2015. It sets out their responsibilities relating to housing and requires them to work closely together on improving outcomes for homeless households. It is not clear whether this has positively affected the prevention of homelessness in Scottish healthcare settings, but it is a clear and welcome statement of intent from the Scottish Government.

Similarly, the 2015 Welsh Government NHS ‘Standards for Improving the Health and Wellbeing of Homeless People and Specific Vulnerable Groups’, sets out expectations for joint working between housing and health settings to improve outcomes for homeless people.

The intersection of homelessness and domestic abuse is complex. Many survivors of abuse leave their housing to escape a dangerous partner. Others are evicted from housing due to a perpetrator’s behavior, such as damaging property, or failing to pay rent. In some cases, once the perpetrator is removed or evicted, the victim of abuse must also have to leave because the housing is no longer affordable. Similarly, a survivor may be unable to pay rent because of actions taken by an abusive partner.

In 2015/16, 6,550 people were accepted as homeless in England by their local authority because of a violent relationship breakdown. This accounts for 11 per cent of all homeless acceptances. In Scotland, the latest figures report 12 per cent of homeless applications were as a result of a violent/abusive dispute. In Wales, 2016/17 data shows that 11 per cent of homeless acceptances were due to a person fleeing or being at risk of domestic abuse.

Our Nations Apart research from 2014 found that 61 per cent of homeless females and 16 per cent of homeless males across Great Britain had experienced violence and/or abuse from a partner. Half of St Mungo’s female clients have experienced domestic violence and one third state that domestic violence contributed to their homelessness.

An All Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness (APPGEH) inquiry heard harrowing evidence from abuse survivors failed by housing agencies when at risk of homelessness. Common problems experienced by survivors include the need to prove ‘vulnerability’ as a result of experiencing abuse, and having to demonstrate a ‘local connection’ to access services.

Scottish Women’s Aid reported some similar issues in Scotland, despite a strong legal safety net and code of guidance for local authorities. In particular, the report highlights a lack of understanding about domestic abuse and its impacts among Housing Options staff.

Homelessness prevention for survivors of domestic abuse must be tailored to the needs and choices of people involved. There are some common approaches to providing help, but no identified programmes with a strong evidence base.

Sanctuary schemes offer survivors help to remain in their home. They provide additional security measures within the home, with details provided to local police to ensure the fastest possible response should further abuse take place. The SCIE study found some evidence of the effectiveness of sanctuary schemes, alongside cost saving data.

Provision of refuges has been a traditional approach to assisting people escaping domestic abuse and relieving one of the most acute forms of homelessness. This kind of emergency accommodation is often the immediate response to provide safety away from a perpetrator. There is no one model of refuge provision, and they can range from individual units of self-contained housing to congregate buildings more akin to hostels.

The APPGEH inquiry into homelessness and domestic abuse heard evidence of some innovative practice at local authority and housing association level. These included schemes to provide reciprocal access to housing for survivors of abuse across local boundaries. Other evidence included housing associations seeking to identify people at risk of homelessness and abuse through their own property management and training of staff. Once again this shows how homelessness prevention can and should be started well before issues reach a local authority housing team.

In Wales, the recent Renting Homes (Wales) Act (2016) enables a joint tenant, who is a perpetrator of abuse, to be removed from the joint tenancy without the joint tenancy failing. This allows the survivor of abuse to remain in the home.

Youth homelessness charity Centrepoint recently published the results of a systematic review of the evidence on approaches to youth homelessness prevention. The report highlights the diversity of services aiming to prevent youth homelessness and many examples of good practice.

Four key principles were identified as important in successfully preventing youth homelessness. Each was seen as a common theme in the available evidence. These were:

In 2007, a UK-wide review of youth homelessness provision reported positive results in the burgeoning Housing Options approach. Then, as is the case now, it was seen as crucial that local authority responses focused heavily on mediation approaches with families. And if necessary, an alternative source of secure housing should be available for young people. The mediation may be best delivered by a third party, rather than the local authority, ensuring that any vested interest in the young person returning home is avoided.

Much of this approach is reflected in the St Basil’s Positive Pathway model, which 66 per cent of local authorities in England report using or developing. The Positive Pathway brings together evidence of good practice, and outlines how agencies should work together in an integrated way.

It aims both to prevent homelessness and to promote a range of housing options to ensure a planned move for young people leaving care or the family home. A recent evaluation of the Positive Pathway model, demonstrates, that it results in improved service provision, better use of resources, and better outcomes for young people.

The 2009, House of Lords ‘Southwark Judgement’ obliged children’s services to provide accommodation and support to homeless 16 and 17 year olds. It also shone a light on the need for better commissioning between local authority children’s services and housing departments.

Immediate access to alternative accommodation is often provided through the ‘Nightstop’ approach. This is an emergency housing provision in private homes whose residents/ families have been carefully vetted and approved by homelessness agencies. The approach has marked success in preventing rough sleeping for young people, and shows promising evidence about the ability of people to move on positively.

All these elements add up to a good body of knowledge about how to help young people at risk of homelessness, but further evaluation and innovation is crucial. As the Centrepoint research states: ‘robust evidence is urgently needed’.

Two notable examples of emerging evidence and innovation are below.

Data relating to homelessness prevention activities in local authorities is recorded in each country, though in different ways and to varying standards across England, Scotland and Wales.

England In 2009, local authorities in England started recording data on people who approached for assistance outside of the statutory framework. They also record how local authorities help people resolve their homelessness before a formal homelessness application has taken place. Referred to as ‘prevention and relief activity’ the statistics show to some extent ‘successful’ prevention action and how this has changed over time. For example, help to prevent homelessness through resolving Housing Benefit problems has increased fourfold since 2010/11.

It is useful to report on the type of prevention and relief activity that local authorities are using. But there is currently no way of assessing the effectiveness of these interventions, the quality of the service provided and the sustainability of the outcomes for households approaching them for assistance.

The prevention and relief statistics are also not able to eliminate duplication when households receive more than one prevention and relief activity within the year. They do not cross reference with the local authority statutory homelessness returns, which would allow double counting to be removed. These data were deemed by the UK Statistics Authority in 2015 to fall short of the standard required for ‘national statistics’.

The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) has prompted the introduction of a new system for local authorities to record prevention and relief data, called ‘H-CLIC’. This is due to report in July 2018 and will provide information about all households owed a prevention duty including reasons why the prevention duty has ended.

In Scotland, homelessness statistics are collected so that each person has a unique identifying number. This allows local authorities to track households/ individuals through the homelessness system and can help identify if they have been homeless before. Local authorities are able to understand how many households made a unique application for homelessness assistance. The system also stops double counting and reports the proportion of households making a repeat application after receiving help. Collecting this ‘HL1’ data is compulsory for local authorities, who must do so from anyone they have reason to believe is homeless (or will be in 56 days).

In 2014 the ‘PREVENT1’ statistics were introduced in Scotland to record housing options activity. This system is fragmented because homelessness prevention sits outside the statutory system. Also, much of the prevention work that happens both within authorities, and more widely via other agencies and housing providers, is in places with no access to the database.

The ability to link both datasets is useful to measure an overall homelessness caseload figure, though there is varied practice in how these are recorded across local authorities.

The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) also brought changes to statutory homelessness statistics in Wales. Statistics are now collected in relation to the number of outcomes, and not by household. This makes it difficult to use the data for some statistical purposes, particularly in attributing the overall homelessness need across the country.

The Welsh system means that each household could have up to three outcomes: prevention; help to secure accommodation (relief); and duty to secure accommodation (discharge). Data is collected on the type of prevention activity used but, similar to the English data, households are not followed through the system. This means there is no way of understanding the proportion of households who experience repeat homelessness and become homeless again after a prevention outcome. Consequently it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of prevention measures.

One further development in the Scottish statutory homelessness statistics is data linking between HL1 and health service data, originally trialled in Fife. This approach has the potential to revolutionise our understanding of what works to achieve positive outcomes for homeless people across public services.

Data linkage and tracking people through homelessness datasets, across Great Britain and in all public services data sets, would show how well (or otherwise) services are meeting the needs of homeless people. It would also show the cost effectiveness of interventions including prevention measures. In the US and Denmark data linkage has been used for some time to explore patterns of service use and the cost associated with them.

In Wales, a four-year data linkage study into the Supporting People programme is running from 2016 and 2020.

Large scale data merging across Britain could facilitate the cost effectiveness of services such as Housing First and CTIs, and explore how to improve prevention services and their integration across statutory services.

Data linkage is vital to fully understand how homeless services meet the needs of homeless people and we strongly recommend expanding and replicating existing successful models of linking data across homelessness, health, criminal justice and other relevant services.

Scenario: Person leaves prison with no available accommodation

Agencies Prison, Community Rehabilitation Company/ Criminal justice social work (Scotland)

Scenario: Person or household flees their home to escape domestic abuse from a known perpetrator

Agencies The police

Scenario: Household leaves Home Office Asylum Support accommodation, following an asylum claim decision

Agencies: The Home Office

Scenario: Young person leaves the care system

Agencies: Local authority children’s services

Scenario: Person is served an eviction notice from a registered social landlord

Agencies: Housing association or other social housing provider

Scenario: Person is discharged from a psychiatric unit or other in-patient stay, following treatment

Agencies: NHS hospital, GP, Local authority adult social care

Scenario: Person is discharged from residential detox or rehabilitation unit

Agencies: Local authority adult social care

The case for fully expanding measures to prevent homelessness is overwhelming in both financial and human terms. The political agenda to prevent homelessness is strong, and still growing.

Lead responsibility for prevention sits with local authority housing teams in England and Wales, with duties to help prevent homelessness set out in law. The picture is similar in Scotland, but on a non-statutory footing. There are inherent problems in this settlement of responsibility.

The actions required to prevent homelessness will be most effective when delivered at the earliest opportunity. By the time a household presents for assistance at a local authority housing team it is likely that opportunities have been missed to resolve the issue. Indeed, in the case of people leaving institutions, some people will no longer be at risk of homelessness, but already experiencing it.

Above are some common scenarios, alongside details of the agencies with the knowledge and ability to help prevent homelessness. In each of these scenarios, at least one agency or organisation is aware in advance of homelessness that the person or household is at risk. Yet the lead responsibility for homelessness prevention falls to local authority housing officers who may have no idea that it is required until it is too late.

Local authority prevention strategies should of course ensure close relationships with other local agencies, but there is nothing to compel them to cooperate in prevention strategies or individual cases. Significantly, people from all sectors – including health, social services, DWP, criminal justice and education – who participated in the extensive consultation to inform this plan, reported that joined-up working is critical in preventing homelessness.

Close partnership working between different sectors was also highlighted as important by participants with experience of homelessness. They emphasised it would ensure people do not fall through the cracks of the system.

Another problem with sole local authority responsibility is that financial rewards for preventing homelessness – eg reducing crime or hospital admissions – often do not benefit the authority. Consequently, there are concerns that if the local authority sees no financial incentive, they may not prioritise prevention activity – particularly in the light of reduced budgets. This can especially affect non-priority households, or people without a local connection, for whom that authority will not owe a full duty for rehousing.

To counter these disincentives and the overall lack of co-ordination, a change in legislation is needed. As set out in Chapter 13 ’Homelessness legislation’, a new duty to prevent homelessness, and to cooperate with local housing authorities in relieving homelessness, should be extended to relevant public bodies. This is in addition to the existing duties on local housing authorities in England and Wales to prevent homelessness (which are also recommended for Scotland).

Such an approach would be bolstered by truly cross-government strategies to end homelessness in the three nations.

This section sets out the necessary changes in policy across all three nations. Actions for government in each nation are set out at the end of this chapter.

To ensure Housing Options is delivered on a stable and consistent footing, it must be brought into the statutory homelessness framework across Great Britain.

Local housing authorities should have a statutory duty to prevent homelessness for all households who are at risk of becoming homeless within 56 days. This duty is already in place in England and Wales.

A mandated set of activities that local authorities should have available to them to help prevent and relieve homelessness should be set out in secondary legislation. This should include:

This duty should apply to all households at risk of homelessness within 56 days, regardless of priority status, local connection, intentionality or migration status.

The duty should set out a balance of responsibilities, recognising that there is likely to be a role for the applicant themselves, local authorities and other public services in successfully preventing homelessness.

There should also be a duty on all relevant public services and agencies to prevent homelessness. As detailed above, other public services will often be aware that someone is at risk of homelessness and have opportunities to help prevent their homelessness, well before they approach a local authority housing team. Placing a duty to prevent homelessness on other public services is critical to ensure that homelessness is prevented for as many households as possible.

CTI should form a key part of national strategies to prevent and end homelessness for groups most at risk of homelessness. This model has been shown to work to successfully prevent homelessness across a variety of groups of people leaving state institutions. CTI should be implemented at scale to prevent homelessness for care leavers, prison leavers, people leaving the armed forces, people leaving asylum support accommodation and people being discharged from hospital.

Sufficient funding is vital to ensure prevention measures are commissioned and successful. Allocations to local authorities should be set out on a long-term and stable basis. Where necessary, other agencies responsible for prevention action should have access to additional funds.

The Centre for Homelessness Impact should be commissioned to fill gaps in evidence relating to homelessness prevention for people at immediate risk, and for groups in proven need of prevention services.

Trials of new methods of preventing homelessness are likely to be needed – especially to prove the effectiveness of housing-led and intensive case management approaches in the UK. The highest standards possible of trialling and evidence collection should be used. The evidence gaps for preventing youth homelessness and homelessness for people who experience domestic abuse are particularly important.

This robust evidence will help local authorities and other relevant agencies commission services more confidently, and plan for successful outcomes.

Data linkage is vital to fully understand how homeless services meet the needs of homeless people. It has the potential to demonstrate the effectiveness and the cost distributions of interventions across the homelessness, health, criminal justice, and welfare systems.

To establish data linkage, gaps in the use of, and access to, data sets across health, homelessness, housing, criminal justice, substance misuse, welfare benefits and employment services must be addressed. Where data linking exists on a small scale or for specific groups (for example in Scotland using ‘HL1’ and hospital admissions data) it needs to be expanded and replicated.

The lack of data on outcomes and success of prevention also needs to be rectified. This can be achieved by introducing a data system that tracks households at every point in their journey. It should also have the ability to record success or failure of prevention through linking to other homelessness data sets.

Such changes must be done in tandem with a national outcomes framework or equivalent. This will allow the comprehensive tracking of the quality, outcomes and effectiveness of homelessness services for individual people. Commissioning decisions and the effectiveness and cost of services will be properly informed as a result.

Recommendations for improved data collection and linkage are set out in full in Chapter 14.

As described above and in Chapter 4, the homelessness sector does not always communicate effectively about prevention.

As experts in the sector, we agree that prevention strategies are essential in tackling homelessness. However, most of our communications emphasise the need for short-term and emergency responses. We fail to describe the opportunities to prevent homelessness in the stories we tell.

In this context, it is no surprise that public attitudes to homelessness are fatalistic. They see the problem as inevitable, and do not recognise prevention as a solution. As a sector, if we want policy choices and investment in prevention, we must assume responsibility for generating positive public responses that will back these political choices.

In order to activate public understanding and support for preventative action on homelessness, evidence from the FrameWorks Institute tells us that the homelessness sector needs to communicate differently. They have widely tested what it might take to improve public responses to homelessness, including how to activate public support for prevention.

The FrameWorks research strongly recommends we communicate stories of homelessness and its impact using a ‘common experience’ frame. A combination of messages, values and stories make up this frame and together they do three important jobs.

First, they highlight our fundamental commonalities – showing that homeless people are human beings and members of society, and not somehow ‘other’.

Second, they communicate the experience of what it is like to be homeless.

And third, they explain how homelessness happens and how systemic solutions can help.

The frame combines these elements. It is crucial that they are used in combination with each other. This is because using one element alone will not be effective and may undermine the attempt to reframe the issue.

Chapter 4 explains these and other proposed changes in detail. Crisis is committed to implementing these in our public-facing materials, and to working alongside the wider homelessness sector to do so. It is clear from the evidence that these changes would allow a more honest account of the preventative solutions proposed in this chapter.

Wider reforms are also necessary to allow for successful interventions.

This chapter has highlighted a number of key strengths within the three homelessness systems across Great Britain. It is clear that the value of intervening early to prevent homelessness is an accepted and agreed aim both politically and among service providers. The Housing Options approach, applied in a flexible and person-centred way, is known to work and should be the cornerstone of local authority prevention.

Standing in the way of a complete and effective approach to prevention are a number of clear issues. Each demands a policy response. The legal entitlements to prevention assistance are making a positive difference in Wales. They need to be extended, effectively funded and bolstered with the integrity of good data.

Homelessness prevention must become the business of a range of public services. This will require cross-government reforms and crucially the large-scale deployment of programmes such as CTI.

Prevention could and should be the first and most important element of a strategy to end homelessness. But it will only be possible with the reforms outlined above in place and an active agenda to improve the evidence of what works for different groups and circumstances.

England/Westminster

Scotland

Wales