Rough sleeping is the most dangerous form of homelessness. It can and must be resolved, for each person experiencing it, and collectively for society.

This chapter details how rough sleeping can be ended. We use evidence of what works from both at home and abroad to tackle it

Rough sleeping is the most visible and damaging form of homelessness. It rightly causes the most concern among the public, decision makers, and advocates for homeless people in the charity sector. Rough sleeping is not usually the first form of homelessness people experience. However, tackling it must be central to any plan to end homelessness, given the extreme dangers posed to people living on our streets.

This chapter sets out how to achieve the first and second definitions of ‘homelessness ended’ as described in Chapter 3 ‘Defining homelessness ended’.

Definition 1 – No one sleeping rough.

Definition 2 – No one forced to live in transient or dangerous accommodation such as tents, squats and non-residential buildings.

As explained in Chapter 2, ‘Public policy and homelessness’, there have been successful attempts to reduce rough sleeping by the Westminster and Scottish Governments. There is also increasing international evidence to supplement the lessons of these recent successes.

This chapter has been informed by a specially commissioned review of the evidence at home and abroad about proven successful attempts to tackle the problem.

Although rough sleeping is the most damaging form of homelessness, it is also the least prevalent and so it is entirely within the power of policy makers and service providers to end it. There has never been more evidence about how to do so.

On any given night, there are an estimated 9,100 people sleeping rough in Great Britain. This figure can be reduced to zero within ten years. But only with the necessary policy changes to prevent further rough sleeping, and evidence-based interventions to rehouse people.

This chapter details the solutions to rough sleeping. It necessarily and intentionally repeats some solutions and recommendations from other chapters. We focus on rough sleeping as an urgent priority and look at it within a wider strategy in each nation. It also details what investment is needed for those solutions to be implemented. Our approach to developing rough sleeping solutions is summarised in the diagram on page 160. A summary of the actions required by each national government is given at the end of the chapter.

The suffering of people who experience rough sleeping is overwhelming. It severely affects their physical and mental health and personal safety.

Mortality rates among homeless people are higher than the general population. Those affected by homelessness are ten times more likely to die than those of a similar age in the general population.2 The average age of death for homeless people is just 47.

Rough sleepers are likely to have an even higher risk of dying. Recent data from people living on London’s streets reveals their average age of death as 44.

The Homeless Link Health Needs Audit in England shows that 88 per cent of rough sleepers report physical health problems. This includes 49 per cent who report a long-term health condition. The physical health problems associated with rough sleeping include higher rates of tuberculosis and hepatitis compared to the general population. Health problems also include skin diseases and injuries following assault on the streets. Very high rates of respiratory conditions among people sleeping rough are common too.

Mental health problems among rough sleepers are very common and often acute. Research from the homelessness charity St Mungo’s shows that more than 40 per cent of people sleeping rough have a mental health problem. It also highlights that those with mental health problems are 50 per cent more likely to spend a year or more on the streets. Rough sleepers report that the experience itself leads to isolation, to stigma and can take a serious toll on their mental wellbeing.

Living on the streets also involves personal danger. Our 2016 study showed that 77 per cent of rough sleepers had been a victim of crime or anti-social behaviour in the previous 12 months.10 This included 30 per cent who experienced violent attacks, six per cent who had been the victim of sexual assault, and 51 per cent who had their possessions stolen.

The experience of rough sleeping for any one person is frightening and devastating; more than 9,000 bedding down every night on our streets is a damning indictment of our society. We are one of the richest nations in the world and we are ignoring the strong evidence and experience of how to solve the problem.

The numbers of people sleeping rough in England, Scotland and Wales are recorded and presented in different ways by governments in the three countries. These official statistics each have flaws in terms of data integrity. The official statistics are detailed in this chapter, alongside an assessment of the methods used to collect the data.

The rough sleeping estimates from the Heriot-Watt homelessness projections research are also presented. They show an estimated 9,100 people sleeping rough in Great Britain on any one night.

As detailed in Chapter 5 ‘Projecting Homelessness’, these figures represent a more comprehensive estimate of the problem and use a range of informed sources. These data sources are used later in the chapter to show the demand for rough sleeping interventions and solutions.

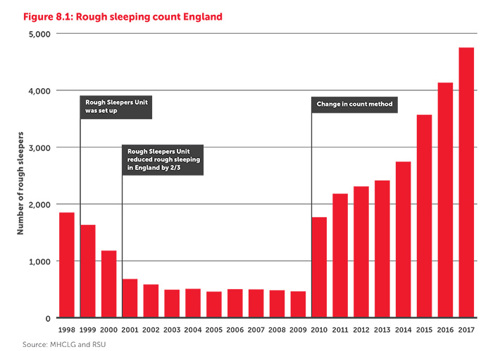

The rough sleeping count for autumn 2017 reported that 4,751 people had been counted or estimated.12 This represented a 15 per cent rise on the previous year, and a rise of 169 per cent since 2010 when the current methodology was adopted, see figure 8.1.

These figures are a combination of numbers of people who have been seen while sleeping, bedded down, or about to do so. They also include people who have been seen living in places not fit for human habitation, such as stairwells or car parks.

These figures are made up of both counts and estimates from local authorities of the number of people thought to be sleeping rough in a local authority area on a ‘typical night’. This night is a single date chosen by the local authority between 1 October and 30 November. It is a snapshot and will not include everyone in the area with a history of rough sleeping. In 2017, 87 per cent of councils estimated and 13 per cent counted.

In 2015, the UK Statistics Authority (UKSA), which oversees the validity of official government data, conducted an investigation into the homelessness statistics. UKSA concluded that government data on rough sleeping does not meet standards required to be considered ‘national statistics’, and that the data falls short in ‘trustworthiness, quality, and value’.

Despite the problems with England’s official figures, there are useful indications within the data of where rough sleeping is most common and of different characteristics of homeless people. For example, we know that rough sleeping in London has consistently accounted for approximately a quarter of the national problem over the previous seven years. We also know that approximately 14 per cent of rough sleepers are women; and that very few people sleeping rough (an estimated 0.1 per cent) are under the age of 18.

While the scale of rough sleeping is unlikely to be accurately reported within official data, the statistics provide an insight into which interventions could tackle the problem.

The CHAIN (Combined Homelessness and Information Network) database in London is also useful. It records multi-agency information, including outcomes for individual rough sleepers. It is through this data that we can track the success of interventions like No Second Night Out (NSNO). This has achieved marked success in reducing the numbers of people who experience a second or ongoing experience of rough sleeping in the capital.

The Heriot-Watt University homelessness projection estimates for rough sleeping suggest a significantly higher level in England. Their estimates consider official data and sources including CHAIN data, household surveys and academic studies. The data reveals a mid-range estimate of 8,000 rough sleepers in England in 2016; projected to rise to an estimated 13,000 within the next decade.

Scotland

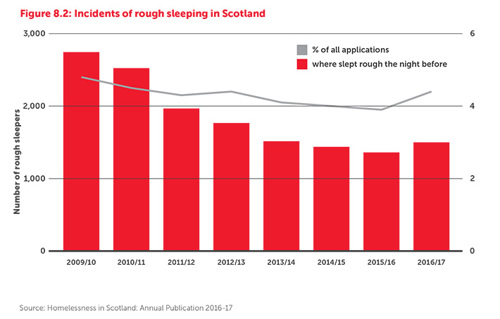

Published rough sleeping figures in Scotland relate to the number of people annually applying for assistance from their local authority. These people will have reported that they slept rough the night before their application and in the prior three months. Latest figures show that in the reporting year 2016/17, 1,500 people slept rough in Scotland. This is a ten per cent increase on the previous year, as shown in figure 8.2.

These figures are a measure of the ‘fl ow’ of people over a year, rather than the ‘stock’ or ‘point in time’ figures in England that relate to a given night. The crucial fl aw in the published data is that only those applying for local authority assistance, who report sleeping rough the night before or in the last three months, will be counted. Those that do not make a homelessness application will not appear in the statistics. Evidence of effective ways of tackling rough sleeping shows that services must go out to people through ‘assertive outreach’ rather than waiting for people to come to them.

Table 8.3: Rough sleeping across the four cities of Scotland

Homelessness projections from Heriot-Watt University estimate that on any given night there are 800 people sleeping rough across Scotland. This represents a fall of 100 people since 2011, and is projected to fall by another 100 people over the next decade, before rising after that. These are more robust estimates, using wider survey data where people report experiences of rough sleeping.

The Scottish Government recently established a Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group to make informed recommendations about tackling the problem. The group has recommended establishing new and more robust methods for gathering and recording rough sleeping data. Recommendations include allowing data to be collected and used from different contributors within the voluntary and statutory sectors. The group also recommends the nuancing of data, allowing different subgroups of rough sleepers/homeless people to be captured. These subgroups should include: women experiencing domestic abuse; LGBT young people; people experiencing relationship breakdown, and people migrating from outside of Scotland.

Although Wales has the smallest rough sleeping population in Britain, the problem continues to increase.

The Welsh Government figures reflect two separate measures. First, local authorities estimate over a two-week period, and second, a count on one night. These measures were most recently conducted in October and November 2017. The two-week estimate reported 345 rough sleepers, representing a ten per cent increase on the previous year. The count reported 188 people, an increase of more than a third compared to the previous year.

The Welsh Government is clear about the limitations of the published data. They point out, ‘there are a range of factors which can impact on singlenight counts of rough sleepers, including location, timing and weather.’ The count carried out in November 2017 in Wales is essentially a snapshot estimate. It can only provide a very broad indication of rough sleeping levels on the night of the count. They also acknowledge that there are limitations to the count in rural and coastal areas, where the sparse population makes counting difficult.

The Welsh Government and the Welsh homelessness charity, The Wallich, have been working together to develop the Street Homeless Information Network (SHIN). SHIN will collect data from a network of organisations across Wales that support rough sleepers. It will combine their data to enable more in-depth, consistent and continual analysis of rough sleeping trends across Wales.

Heriot-Watt University projection figures for Wales estimate a 2016 figure of 300 rough sleepers across the country. This reflects a rise of 50 per cent since 2011.

Table 8.4: Projections of rough sleeping across Great Britain

See full PDF

The evidence base

In 2017, Crisis commissioned Cardiff University and Heriot-Watt University to carry out an international evidence review of ‘what works’ to end rough sleeping. The objective was to identify the interventions to be used and/ or expanded.

The review was published in December 2017. It examined a range of different interventions and suggested five key themes to help underpin the approach taken to prevent and end rough sleeping.

In addition to the 2017 Cardiff University and Heriot-Watt University ‘what works’ review of rough sleeping, we also commissioned the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE) to undertake a broader examination of the evidence on homelessness interventions. This piece of work also helps inform these recommendations.

Supported accommodation Supported accommodation and homeless hostels are currently the backbone of homelessness services to address rough sleeping, helping people recover and rebuild their lives.

There are 35,727 bed spaces available in homelessness accommodation projects across England. This figure does not include the bed spaces available in emergency shelters (eg winter night shelters) and in very specialist accommodation for people with substance misuse, mental health needs and a history of offending.

In Scotland, most homeless households are housed in self-contained temporary furnished accommodation, including former rough sleepers. However, 4,237 households continue to live in hostels, bed and breakfasts and other accommodation. These can vary considerably in quality and levels of support provided, and are often used to house those with more complex needs. Data on the number of bed spaces in Wales is not readily available.

Supported accommodation varies substantially in relation to the size and support provided. For example, the term can describe very basic hostels simply providing people with an emergency bed to get them off the streets as quickly as possible. They offer very little additional support.

But more commonly, supported accommodation for homeless people tends to be clustered temporary accommodation. Providers often deliver a wide range of services to people before they move into permanent housing. The support could include assistance regarding mental and physical health and substance misuse, and pre-tenancy training and employment support. For people with significantly higher support needs, more specialist forms of temporary supported accommodation can act as a longer-term housing option.

Over the past ten years, hostels and supported housing units have been generally decreasing in size. More than half the projects in England have 20 bed spaces or fewer, providing scope for a more personalised form of support. In 2016, two thirds of people (66%) who left homeless accommodation in England stayed there for six months or less. A quarter (26%) stayed for less than a month and three per cent stayed for two years or more.34 Research shows a similar trend in Scotland.

In some supported accommodation, a ‘staircase model’ is applied. This means that someone must engage with support services and demonstrate housing readiness before they can move to permanent accommodation. There is little evidence available on the extent to which this model is currently applied within the UK context.

Our 2017 ‘what works’ review found limited UK evidence evaluating the effectiveness of supported accommodation in moving people into permanent housing and ending their homelessness. The review identified a clear need to expand the evidence base.

Most evidence comes from the hostel system outside the UK. This can vary substantially and often does not provide as personalised packages of support. Consequently, this evidence does not usefully assess the impact of hostels and supported accommodation on ending homelessness in Great Britain.

Key informants for the review could see a role for supported housing. They said when provided as a longer-term solution outside of a ‘staircase model’, it can work well, although it is currently often hampered by a lack of move-on accommodation.

A study from England in 2011, identified in the review, interviewed 400 people. It covered them moving from temporary (a range of types) to permanent accommodation. The focuses were: at the point before the people moved, six months after their move, and then 15 to 18 months afterwards. Seventy-three per cent of respondents remained housed in the original accommodation in which they were rehoused across the 18-month period, and eight per cent moved to a new tenancy.

The ‘what works’ review found that people with high support needs are sometimes forced to go into large hostel accommodation because of a shortage of suitable places. This can exacerbate the problems they experience, and also present difficulties for other people living in the same accommodation project.

There were also several reports recording people who would rather stay on the streets than use hostel accommodation. In 2017, the homelessness charity Groundswell conducted a peer-led research project for the Hammersmith and Fulham Commission on Rough Sleeping. As part of this project they interviewed 108 people with recent experience of sleeping rough.

Of the 108 interviewees, only two people stated that they wanted to live in a homeless hostel. In two separate focus groups, the consensus was that people would prefer to be in prison rather than in a hostel. Resistance to moving into hostels was common. They explained that the chaotic environment, poor quality accommodation and limited opportunities for moving on were key deterrents.

In 2016, 30 per cent of people in accommodation projects in England were ready to move on, but had not yet done so. Of this group, 27 per cent had been waiting for six months or longer. In Scotland, the average duration of stay in temporary accommodation is 24 weeks, and 12 per cent of households remain there for a year or more. This applies to all households living in some form of temporary accommodation.

This is largely due to a lack of affordable move-on accommodation. More recently there has been a shift towards the practice of harm reduction in hostels and supported accommodation. This places less emphasis on the need for complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol before someone can access permanent accommodation.43 Most hostels link people to drug and alcohol services. A project would not normally evict someone because they had a drug and alcohol misuse problem.

Last year, however, the Homeless Link Annual Review of Single Homelessness Support in England found the following:

Further evidence from the UK suggests that hostel staff spend a disproportionate amount of time managing the behaviour of people with highly complex needs. This can stop them offering more meaningful one-to-one support.

This evidence comes at a time when investment in homelessness accommodation has been declining. Last year 39 per cent of homeless accommodation projects in England reported a decline in their funding from the previous year.46 Aside from Housing Benefit contributions, funding for homelessness accommodation at a local level comes from housing related support (formerly known as Supporting People).

While spending specifically on homelessness has increased (by 13%) since 2010, reflecting the priority given to this area by government, overall spending on housing dropped by 46 per cent in real terms, with an even larger cutback (67%) in the Supporting People programme. Homeless accommodation projects must now provide services to an increasing number of people despite declining budgets.

The Welsh Government’s decision to merge Supporting People with a wider series of non-housing grants and remove longer-term certainty about the funding level presents a similar risk, and is an area of major concern to the sector. To date, similar scale cuts have not occurred in Scotland. This is largely because temporary accommodation is primarily funded through Housing Benefit, and homelessness applications have been increasing.

Housing First Housing First is the most important innovation in homelessness service design in the last few decades. It is proven to end homelessness for at least 80 per cent of people with high support needs.

The Housing First model prioritises rapid access to a stable home, from which other support needs are addressed through coordinated and intensive support. Permanent housing is provided without a test for housing readiness. Maintaining the tenancy is not dependent on the tenant using support services.

Housing First is based on the principle that housing is a human right. It focuses first on immediate access to a settled and secure home, placing this above goals such as sobriety or abstinence. The model is specifically tailored for homeless people with complex needs. Housing First centres on choice and control – giving rights and responsibilities back to people who may have been repeatedly excluded. The model depends on giving access to stable and affordable housing. But it also means people can use a wide range of services to get personalised support when they need it and in their chosen format.

There is overwhelming evidence of Housing First’s positive role in helping people with complex needs keep permanent accommodation and improve other issues related to their health and wellbeing. The volume of evidence far exceeds that of any other intervention, and includes a mix of large-scale Randomised Control Trials (RCTs) and smaller studies.

Housing First has particularly high housing retention rates of 80 per cent. It also has led to reductions in offending and improved mental health. It has not been shown to produce the same results in relation to physical health, though there is no reason to suggest these outcomes are any worse than in traditional approaches.

Housing First was developed in the US by the organisation Pathways to Housing, and is being delivered across the world. Perhaps the most striking successful example is in Finland. Here, Housing First, as part of a wider homelessness strategy, has reduced rough sleeping to very low numbers; all forms of homelessness have reduced to a ‘functional zero’.

Key to Housing First’s large scale implementation in Finland has been the role of a national housing association, the Y-Foundation. This organisation specifically focuses on providing housing to people who have experienced homelessness. Between 2008 and 2015, approximately 3,500 new dwellings were built for people experiencing homelessness. And a total of 350 new social work professionals were employed to work specifically with them. According to FEANTSA, the European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless, Finland is the only European Union (EU) country in which homelessness continues to decrease.

In Denmark, the national Homelessness Strategy from 2009- 2013 introduced one of the first large-scale Housing First programmes in Europe. It housed more than 1,000 people, and achieved housing retention rates of between 74 per cent and 95 per cent.

Further evidence of high levels of housing retention is found across Europe, North America and Australia. For example, the Canadian RCT study into the two-year ‘Chez Soi’ programme found that Housing First service users spent 73 per cent of their time stably housed. This is compared to 32 per cent of those receiving treatment as usual in the Canadian homelessness system.

Similarly, two published studies on the Street to Home project in Australia show that after one year 95 per cent of clients had kept their housing in Brisbane. In Melbourne, 80 per cent had been housed for one year or longer. There are high tenancy sustainment rates for international Housing First projects. However, we cannot compare its success to studies measuring projects alongside treatment as usual outcomes in Great Britain. This is because the treatment is not always comparable with services offered across different parts of Britain. In addition to strong housing sustainment rates, Housing First schemes throughout the world have also been shown to have wider positive impacts on people’s lives. The Street to Home Melbourne evaluation found that there was significant improvement in the participants’ physical and mental health in the first 12 months. Sixty three percent of people said their general health was better, and 24 per cent reported moderate to extreme bodily pain after 12 months, compared to 54 per cent when first interviewed. The number of participants hospitalised dropped by 21 per cent. Participants were regularly interviewed, starting at three months before being found a home and up until two years afterwards.

In a study of five projects in Europe, improvements in mental health problems were reported for most participants in Amsterdam (no exact figures supplied) and Glasgow (50 per cent). In Lisbon there was a 52 per cent reduction in participants being admitted to psychiatric hospitals from the start of the project to the three year follow-up.

Both qualitative and quantitative research shows that Housing First participants are less likely to be involved in crime. Woodhall-Melnik and Dunn report in their systematic review that the evidence on Housing First and reductions of criminal activity is very strong. Anti-social behaviour also seems to decline, but is far less studied in the literature.

The evidence from Housing First projects in the UK is largely in line with international data. It shows how, if adopted more widely, this approach could significantly reduce homelessness for people with high level needs, as well as improving health and wellbeing outcomes.

In 2015, the University of York published findings from a study of nine Housing First services.68 They found that 74 per cent of current service users had been successfully housed for one year or more. Data collected from 60 Housing First service users showed that:

For a full exploration of the potential and evidence base for Housing First, see Chapter 9 ‘The role of Housing First in ending homelessness’.

Street outreach teams are often the first point of contact for rough sleepers. They work to move people off the streets as quickly as possible and help them access support services and accommodation.

No Second Night Out (NSNO) is an initiative, which has been widely rolled out across England since 2011 and aims to provide a place of safety for assessment of need, emergency accommodation and reconnections for people back to their community. It primarily works to help move new rough sleepers off the streets as quickly as possible often using a single service offer. Outreach services, to help identify people on the streets, is one of the key elements of the approach.

For rough sleepers unable to prove a local connection, it is most likely that the offer will be a reconnection either within the UK, or back to their country of origin. The aim is that no rough sleeper should spend more than 72 hours at a NSNO hub, where they can access emergency accommodation along with washing facilities and food where necessary.

Similarly, while evidence on reductions in substance misuse is more mixed, on balance the literature demonstrates that Housing First is equally and sometimes more effective than a treatment-first approach.

At present, there is relatively limited evidence regarding the intervention, with only smaller scale evaluations, which have focused on short-term outcomes. NSNO is, however, effective in helping to find people temporary accommodation.

Rates of securing and retaining accommodation tend to be higher in London than in the rest of England. But evidence suggests that more favourable reports, relating to the support and aftercare received, come from people using the service outside of London71 compared with those in the capital.

The ‘what works’ review found that service providers recognised that NSNO needed to serve a wider client group than those who are new to the streets. Some areas have widened the eligibility criteria to provide help for longer-term rough sleepers.

The ‘what works’ review also considered the role of more assertive forms of outreach. Assertive outreach teams aim to work with people sleeping rough for a long time and have the highest levels of support needs. The teams use an integrated model of support, drawing on a range of services including drugs, alcohol and mental health.

The primary objective of assertive outreach is to rehouse people in permanent accommodation. Teams work with people using an open ended and persistent approach. This is not to be confused with coercive or punitive approaches.

There is some positive evidence on the impacts of assertive outreach, including evaluations of the Rough Sleepers Unit (RSU) and Rough Sleepers Initiative programmes in England and Scotland, and of Street to Home in Australia. The use of the approach under the RSU contributed to reducing the number of rough sleepers by approximately two thirds within three years.

In addition to a more personalised assertive form of outreach service, the review also identified strong evidence for using personal budgets to support rough sleepers. A personalised budget is an agreed amount of money allocated to someone by a local authority, or other funding stream. It follows an assessment of the person’s housing, care and support needs and is designed to help resolve their homelessness.

Personal budget use was found to be particularly helpful for long-term rough sleepers with high support needs. The budgets were also very helpful in supporting people to move into accommodation and are associated with long-term savings for a range of public agencies. The report highlighted the clear need for greater investment in personalised budgets for rough sleepers and the need for more guidance for those working in the homelessness sector on using them.

By the late 1980s rough sleeping had visibly risen in London and other cities. No official data on levels of rough sleeping were available, but by 1990 homelessness charities estimated that 3,000 people were sleeping rough on any one night. Locations such as ‘Cardboard City’ next to Waterloo Station in London had grown in size and notoriety, and there were reports of ‘shanty towns springing up around the country’.

In 1990, Housing Minister George Young established the first Rough Sleepers Initiative (RSI), which was a three-year programme for London. It involved £30 million of funding to increase outreach work and provide emergency hostel beds and other forms of temporary and permanent accommodation for people sleeping rough. This was extended for another three years in 1993, and an additional £60 million allocated.

By this time political attention and competition on the issue had increased, with the Labour Party stating that homelessness was ‘the visible symbol of all that was wrong with our country’.

In 1996, as attention turned to a third phase of the RSI, ministers were faced with the need to extend the programme and funding outside London. But the lack of data about the geography and scale of rough sleeping made it difficult to allocate budgets reliably. From 1996, local authorities were asked to provide annual estimates to the Westminster Government and so the first ‘official’ estimates of the scale and distribution of rough sleeping were made.

The change of government in 1997 saw a continuation of the work to tackle rough sleeping. The Major Government handed the lessons of the previous seven years to the Blair administration, alongside a new baseline of data and data collection from which to progress.

In 1998, the newly-formed Social Exclusion Unit published a report into rough sleeping which, to some extent, broke from previous thinking on the issue. The report diagnosed causes to the problem that were wider than a lack of access to housing. This social exclusion agenda sought to tackle structural factors. These included unemployment, low incomes, intergenerational poverty, and individual impacts such as mental health, addiction and family breakdown.

With this approach came newly prescribed solutions. They included prevention measures for care and prison leavers, and a focus on multiagency action at a local level,80 overseen by a national coordinating body. And so, in 1999, the RSU was established and handed the target of reducing rough sleeping in England by two-thirds by 2002. The then deputy director of Shelter, Louise Casey, was appointed to lead the unit.

The RSU achieved its target a year early. It did this by applying a range of methods. These included expanding hostel provision, hiring new specialists in mental health and addiction services and establishing outreach teams to contact and assess rough sleepers. It also particularly focused on preventing rough sleeping among those leaving the armed forces, the care system, and prison.

Crucial to the success of the RSU was the political importance and authority ascribed to both the target to reduce rough sleeping, and of the RSU itself. It was given cross-departmental authority in Whitehall, and a reporting line to the Prime Minister.

The Scottish Rough Sleepers Initiative was established in 1997. In 1999 a target was set to make sure no one had to sleep rough in Scotland by 2003. Because of the initiative, the numbers of people sleeping rough that presented to services fell by over a third between 2001 and 2003.

While the target was not met, the initiative led to enhanced support in cities, while in some areas rough sleeping services were set up for the first time. The initiative also drove political and cultural changes within local authorities. This led to a much stronger strategic focus on rough sleeping and homelessness at both local and national level.

A duty to provide immediate emergency accommodation to all those with nowhere safe to stay

Problem

Many rough sleepers and those at risk of living on the streets are not entitled to housing or emergency accommodation.

In Scotland, all eligible households are entitled to temporary accommodation until the council can make them an offer of settled housing.

No such provision exists for households not in priority need in England and Wales, even when someone is already sleeping rough or at immediate risk of doing so.

Solution

Chapter 13 ‘Homelessness legislation’ details the ideal legal framework for tackling homelessness and makes clear that England and Wales should follow Scotland’s lead in abolishing priority need. This change would entitle rough sleepers to accommodation and a range of other benefits. It is not realistic however, to imagine this happening immediately.

Until priority need is abolished, there is an urgent need to protect people from sleeping rough. This should be via a local authority duty to provide emergency accommodation for anyone who is homeless and would otherwise have nowhere safe to stay. This measure was considered in the development of both The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017) and The Housing (Wales) Act (2014). However, it was discounted on both occasions despite the obvious and growing need to tackle rough sleeping.

Impact

This change would entitle 8,300 rough sleepers (on a given night) in England and Wales access to temporary accommodation for 56 days. This provides a window of time for outreach and navigator teams to work with someone to prevent them sleeping rough and to move them into alternative accommodation. In terms of timescales, in Wales there is already a clear gap in the legislation with regards to this group. Consequently, the Welsh Government should be looking to make this change immediately.

In England, we would recommend that this new duty is considered as part of the government’s forthcoming rough sleeping strategy.

Responsibility for change

In addition to legislating for the new duty, relevant government departments in England and Wales would be responsible for introducing and funding duties to provide emergency accommodation for people with nowhere safe to stay.

Problem

Many rough sleepers report asking their local authority for help before they slept out. Research carried out by St Mungo’s found that 33 of the 40 rough sleepers they interviewed had slept rough the night after asking a local authority for help.

In 2015/16, half of 672 UK nationals who used the No Second Night Out service had asked councils for help in the 12 months before they started sleeping rough.

This shows that opportunities to provide advice, assistance and support to prevent people sleeping rough are routinely being missed.

Solution

The Welsh and the Westminster Governments should provide local authorities with additional funding to scale up No First Night Out (NFNO). NFNO works with those at imminent risk of rough sleeping, to ensure they avoid a night out on the streets. The project utilizes a network of private rented sector partners to deliver housing solutions to meet a variety of needs.

An important element of the project is the collection of detailed data on individual journeys into homelessness. Using this data, the boroughs have been able to create categories of new rough sleepers. These have been used to determine the most appropriate response to end their homelessness.

Interventions have included intensive casework in the form of one-toone support, mediation and gaining accommodation in the private rented sector. After its fi rst six months, the pilot extended to fi nding potential clients via outreach work in the community. This was through, for example, job centres, libraries and the Citizens Advice Bureau.

An evaluation of the pilot in 2016 found that this approach was eff ective in identifying the predictable routes people may take in being at risk of or experiencing rough sleeping.88 With more certainty about these routes, the local authorities have tailored their prevention activities more eff ectively.

Impact

Extending the delivery and reach of NFNO would help encourage the culture change needed for English local authorities to meet the new duties in The Homelessness Reduction Act (2017). This is particularly regarding assisting single people into accommodation, and enabling Welsh local authorities to meet their duties under The Housing (Wales) Act (2014).

Local authorities should ensure that Housing Options services are available in settings like day centres that people who are at risk of, or are already, sleeping rough, are most likely to visit.

Responsibility for change

The Welsh and Westminster Governments would be responsible for providing funds for local authorities to deliver a NFNO approach in areas with a rough sleeping population.

Problem

Certain traumatic life events and transitions can put people at much greater risk of homelessness and rough sleeping. These transitions include the points at which people leave or move on from a state institution. In many cases the exit points are predictable and so offer an opportunity for early intervention to prevent rough sleeping. These include people leaving prison, the armed forces, hospitals, and moving on from the care system.

Homeless and formerly homeless people told our national consultation undertaken to inform this plan that a lack of support to help people moving from either prison or care services is a significant cause of homelessness.89 They reported moving into chaotic hostels when they were released from prison, and finding themselves trapped in the homelessness system without the support to move on and achieve stability. The importance of providing advice and ‘through the gate’ support to help prevent homelessness for people leaving prison was also highlighted in the consultation.

Research has shown that one third of care leavers become homeless in the first two years after leaving care92 and 25 per cent of all single homeless people have been in care at some point in their lives.

Similarly, homelessness is a key issue for survivors of domestic abuse. In 2016, 90 per cent of women in refuges were reported to have housing needs. In 2015, 35 per cent of female rough sleepers left their homes due to domestic abuse. In 2016/17, 6,650 people became homeless because of a violent relationship breakdown; accounting for 11 per cent of all homeless acceptances.

Twenty per cent of prisoners surveyed in 2014 said they had no accommodation to go to on release. Ministry of Justice (MoJ) research from 2012 found that 60 per cent of prisoners believed that having a place to live was important in stopping them from reoffending in the future.

The MoJ reported that 79 per cent of prisoners homeless before entering custody were reconvicted in the first year after release, compared with 47 per cent of those who were not homeless.98 Scottish Government research from 2015 found that difficulties finding and retaining accommodation for people who had served short prison sentences is likely to increase their chances of reoffending.

The Housing (Wales) Act (2014) removed automatic priority need for ex-offenders. Although at the same time the Welsh Government agreed a national pathway for people leaving the secure estate. However, senior Welsh Government officials have accepted that the pathway had not been consistently or widely well implemented.

Solution

National governments should ensure that Critical Time Intervention (CTI) forms a key part of national strategies to prevent and end homelessness for groups most at risk and that sufficient funding is made available to take this model to scale.

CTI is a time-limited, evidence-based practice that supports people who are vulnerable to homelessness during periods of transition. It is a ‘housingled’ approach, providing rapid access to permanent accommodation. An intensive case management approach addresses the needs of people once they have security of accommodation.

The SCIE study identified several groups of people leaving institutions for whom tenancy sustainment is significantly increased through the CTI model. These included armed forces veterans, patients being discharged from hospital, young people, and prison leavers. Homeless Link reported that CTI as a targeted approach ‘could arguably be transferred to any vulnerable group’.

The CTI model is based on moving through clear, time-limited phases that are agreed and appropriate for the programme of support. A case manager will start to build a relationship while the person is still in an institution, such as prison, hospital or emergency housing. Consistent face-to-face contact with a case manager, and the security of housing offered have been identified as critical measures of success for the intervention.

Impact

CTI has been widely adopted in the US, and in various European contexts, particularly in Denmark where the success rate for people maintaining their housing is 95 per cent.

There are also several models and interventions in the UK which, using CTI principles, have worked well to reduce the risk of homelessness and rough sleeping.

A 2012 report from Homeless Link and St Mungo’s found that more than 70 per cent of homeless people had been discharged from hospital back onto the street.

In response, the Westminster Government set up a £10 million Homeless Hospital Discharge Fund. The fund’s key aim was to secure safe discharge from hospital after treatment and secure appropriate facilities for those requiring ongoing medical support to allow time for recovery.107 Fifty two projects were put in place which varied considerably in terms of size and target client group. But all featured partnership working across health and housing and a link worker that helped people secure and sustain accommodation and get help from other support services.

Overall 33 projects returned complete data:

It should be noted however that despite successful outcomes, services found it very difficult to get Commissioning Groups (CCGs) after the Hospital Discharge Fund from Central Government came to an end.

In North Wales, a study into the housing and support needs of people leaving prison revealed strong findings about the need for on-going resettlement support upon release. This was in many ways akin to the CTI model.

Recent recommendations from the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group in Scotland have also stressed the importance of the key principles of CTIs in reducing rough sleeping. These included ‘rapid rehousing’ to be adopted by default across Scotland. Recommendations also stated that quick agreement of plans is vital in protecting people from homelessness who are at highest risk of rough sleeping. These include people leaving public institutions such as prison, mental health services and the armed forces. The Scottish Government and relevant partners have also developed the Scottish quality standards housing advice, information and support for people in and leaving prison (SHORE). This is to help ensure that all prisoners can move into settled housing when they are released from custody.

People with lived experience of homelessness who participated in the national consultation undertaken to inform this plan also emphasised the need for a system designed to move people through quickly and efficiently.

Strictly enforced time limits and regular updates are required to ensure people are not left stuck in limbo.

Responsibility for change

To underpin funding for CTI, the Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments will need to strengthen their respective homelessness legislations by introducing a new ‘duty to prevent homelessness’ on relevant public agencies, as explained in Chapter 6 ‘Preventing homelessness’. This would require public bodies in contact with people at risk of homelessness to take reasonable steps to help prevent and resolve someone’s homelessness.

Problem

Local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales are required to publish strategies addressing homelessness in their local area.

The Homelessness Act (2002) requires each local authority in England to publish a homelessness strategy, based on the result of a review, every five years. The strategies were intended to ensure that local authorities were not simply focused on finding people accommodation. The focus was on early intervention to prevent people from becoming homeless or sleeping rough in the first place. However, local authorities can opt out of creating a homelessness strategy under section 6 of The Local Government Act (2000). This Act permits the Secretary of State to dis-apply the requirement to prepare, produce or publish any plan or strategy if they are satisfied that it is not appropriate. This includes the duty to compile a homelessness strategy.

A similar duty to produce a strategy is set out in The Housing (Scotland) Act (2001). Under this Act, Scottish local authorities are expected to prepare and submit strategies for preventing and alleviating homelessness in their area to Scottish Ministers when required. Local authorities however, are only required to publish these strategies every five years.

The Housing (Wales) Act 2014 also contains a duty requiring local authorities to produce a homelessness strategy in 2018. They must then produce a new homelessness strategy every fourth year after this within guidelines provided in the Code of Guidance (2016).

Rough sleeping should always be featured in such strategies where needed. However, the strategies themselves are not required to detail the amount of housing and support required for the actual rough sleeping population.

Solution

A revised approach to homelessness strategies at a local level is required to ensure a housing-led approach to rough sleeping. Strategies should be principally driven by key performance targets for the provision and accessibility of affordable permanent housing stock for people experiencing homelessness and support services. Local homelessness strategies should help inform targets from national government for the provision and accessibility of affordable housing.

This precise approach, delivering housing-led solutions for every single rough sleeper, aligned to robust data collection about the problem, has been fundamental to successes in reducing rough sleeping in other countries, and is a key element in Finland’s dramatic reduction of homelessness.

Impact

The principal benefit of this recommendation would be to ensure that permanent housing stock is made available for rough sleepers (and other homeless people). Publication of key performance targets by national governments will be an important driver to help deliver the supply needed at pace to reduce rough sleeping. The increase of rough sleeping across Great Britain, should make this a priority reform for each of the three governments.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments would be responsible for placing a new duty on local authorities to publish an annually updated homelessness strategy and report on key performance targets.

Problem

As detailed at the start of this chapter, there are serious flaws in the data collection and calculation of rough sleeping figures in England, Scotland and Wales. This fundamental problem inhibits attempts to understand and respond to the true scale and nature of rough sleeping.

CHAIN database

The most robust and comprehensive rough sleeper data set in Great Britain is the London CHAIN system funded by the Greater London Authority. The database is able to collect flows of rough sleeping. These flows allow outreach teams and services to know if someone is new to the street, a returner or a long-term rough sleeper. Demographic information is collected, but other data is collected too. This includes details about support needs, reason for homelessness, if they have previously been placed in homelessness services (short and long-term) and prior rough sleeping experience.

While the CHAIN database is the most comprehensive data set on rough sleeping, it has the following drawbacks.

Solution

A more robust and comprehensive system for recording rough sleeping is required in England, Scotland and Wales. A data recording system should measure annual flow as well as point in-time counts. It should also be linked to statutory homelessness data to show the interaction of rough sleepers with prevention and relief services.

To deliver this more robust approach, the following will be required.

Problem

Assertive outreach is critical to an evidence-based approach to tackling rough sleeping, but the approach is not delivered consistently or at the scale required.

Despite the growing number of people sleeping rough, homelessness charities report a decline in assertive outreach provision since 2009. This is particularly in areas of the country that do not have a large metropolitan centre. In Scotland, sector experts have also acknowledged a lack of an assertive outreach model.

A recent Freedom of Information request from Crisis found that in all areas in England, except the West Midlands, local authority spending on outreach services increased between 2013/14 and 2016/17 (an average of 17%). This is to be expected given that the number of people sleeping rough has increased by almost 100 per cent during the same period. Similarly, during the same period local authority spending on outreach services in Wales increased by 17 per cent as the number of people sleeping rough has increased.118 Funding in Scotland decreased by five per cent, despite the number of rough sleepers increasing by 10 per cent in the last year.

In 2016, St Mungo’s carried out an investigation into the provision of specialist mental health outreach workers. They found that a significant number of specialist mental health and homelessness teams, established in London under the Homeless Mentally Ill Initiative (HMII), had been disbanded. The HMII was launched in 1990 by the then Department of Health in response to the high numbers of people with mental health problems sleeping rough in London. The funding was used over a three-year period to deliver specialist outreach teams, supported accommodation and move-on housing.

The NSNO approach, widely rolled out across England since 2011, has been praised for moving new rough sleepers off the streets quickly. However, service providers are concerned about its ability to provide a suitable offer to people with higher support needs who have spent longer on the streets.121 In many parts of the country the NSNO approach constitutes a single service offer. This could be a reconnection offer or placement in temporary or permanent accommodation. If the rough sleeper declines the offer, the service is not required to make them another one. The purpose is to reduce the risk of someone continuing to sleep rough with the expectation of getting a better offer. However, this may not be successful for the most entrenched rough sleepers who need a more personalised and flexible approach.

Solution

The Scottish, Welsh and Westminster Governments should provide local authorities with additional financial support to expand assertive outreach services. The aim is to provide robust and personalised support for rough sleepers, helping them move off the streets as quickly as possible. The Westminster Government has recently launched a new Rough Sleeping Initiative, which will target £30 million of funding for 2018 to 2019 to local authorities with high levels of rough sleeping. This funding will partly be spent providing a more specialist assertive form of outreach work. The Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group in Scotland has also recommended a more assertive form of outreach to tackle rough sleeping.

The primary aim of assertive outreach is to end someone’s homelessness, often through moving them into a permanent home of their own. Assertive outreach teams place a greater emphasis on an integrated approach to delivering support. They use a multidisciplinary team, including mental health and drug and alcohol specialist workers. They also ensure rough sleepers have swifter access to legal, benefits and employment support.

Assertive outreach workers should be expected to direct most rough sleepers to the services they need away from the streets. For those people who have been rough sleeping on the streets for longer and have higher levels of needs, assertive outreach will involve giving them support in situ.

Assertive outreach works best when it is flexible and persistent, when the rough sleeper cannot ‘fail’, and where there is a meaningful offer of housing (including Housing First if necessary). Persistence is vital, and the professional training and reflective practice necessary requires specialist skills. The reality for many rough sleepers is that they will have experienced trauma in a variety of ways, and so a psychologically informed approach is vital.

Common successful elements of assertive outreach include peer mentoring through the outreach team, specialist mental health assessments, and flexibility to accompany the rough sleeper to accommodation and other venues. The importance of using peer mentoring to help people navigate homelessness and other support services was strongly emphasised by people with lived experience in the national consultation undertaken to inform this plan.

Assertive outreach must not be confused with enforcement, and must avoid authoritarian or coercive approaches. Our research found well targeted enforcement with genuinely integrated support can be effective at stopping anti-social behaviour and be a catalyst for helping rough sleepers move away from the street. However, if used in the wrong way, and without an offer of settled accommodation and support, it can be detrimental. Enforcement measures alone can displace rough sleepers. This leaves them marginalised and excluded from much-needed support services and potentially pushes them into even more danger.

Impact

In the early 2000s, the RSU adopted an assertive outreach approach (delivered through Contact and Assessment Teams), which proved highly effective. This approach was delivered alongside the expansion of some emergency accommodation. The RSU had marked success, reducing the number of people living on the streets by two thirds.

While extremely successful in the short term, only six per cent of people assisted by the RSU in England went straight from the streets into permanent housing. More than 40 per cent of those helped into accommodation returned to the street. By comparison, the assertive outreach team ‘Street to Home’ in Brisbane linked rough sleepers with permanent accommodation. Only seven per cent of tenancies broke down, and in most instances these tenancies were then transferred to alternative housing.

The primary purpose of assertive outreach models must be to move people into permanent housing.

Responsibility for change

An integrated assertive outreach package of support for rough sleepers via a multi-disciplinary team will be best achieved by local authority teams sharing budgets and responsibilities, particularly across health and homelessness.

A recent Freedom of Information request conducted by Crisis found that the Homelessness Prevention Grant is the main source of funding for outreach services. Another source is local authority budgets. Of the 118 local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales that returned data regarding outreach service funding, only seven (in England) reported receiving any public health, NHS or Clinical Commissioning Group funding. Only three local authorities reported receiving any funding from adult social care services.

To meet the shortfall in funding for assertive outreach, the relevant parts of government will need to allocate funds. In England, this is the Department of Health and Social Care, the MoJ and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). In Scotland, this will involve Scottish Government officials from health and social care, housing and social justice and safer communities. In Wales it will involve the Local Government and Public Services Group and the Health and Social Services Group, working with colleagues in non-devolved agencies.

Problem

The ‘what works’ review highlighted the key role of personalised budgets in delivering a person-centred approach, for longer-term rough sleepers with higher support needs.

A personalised budget is an agreed amount of money allocated to someone by a local authority, or other funding stream. It follows an assessment of the person’s care and support needs and is designed to meet agreed outcomes.

There are many positive impacts of this approach beyond housing. These include:

In 2008, the then Department for Communities and Local Government published its rough sleeping strategy document No One Left Out, which committed to piloting personalised support to long-term rough sleepers. Consequently, in 2009 four pilot projects were funded in London, Nottingham, Northampton, and Exeter and North Devon.The London and Exeter pilots were subsequently extended beyond the pilot period.

In 2011 the Welsh Local Government Association Homelessness Network funded five personal budget pilot projects in Cardiff, Newport, Swansea, Bridgend and Anglesey/Gwynedd.

Evaluations of personalised budgets in London and Wales concluded that they were successful, but could only be replicated and expanded across England and Wales if additional funding was made available. This has not yet happened.

Solution

A funding mechanism for accessing individual budgets for rough sleepers is required in all three nations. It is sensible to allocate funds proportionately to the areas with highest number of rough sleepers who require this approach. In Scotland, the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group has recommended that the Scottish Government establish a national personalised budget fund. This can be used by local teams based on reliable data about the nature and number of rough sleepers in their area.

The ‘what works’ review found that personalised budgets cost £3,000 per person in England and £2,000 per person in Wales.130 This excluded the costs of delivering the personalised budgets programme via a support worker.

Responsibility for change

National governments, with input from relevant departments should set up a fund for personal budgets and allocate this to local authorities.

Problem

Several of the measures outlined above require local authorities to provide a robust and personalised support package to rough sleepers once rehoused. In 2013 the Scottish Government introduced a housing support duty to homeless households. This helps provide statutory backing for such measures, although The Homelessness Monitor Scotland (2015) has highlighted the limited impact of the legislation to date. No such provision exists in England and Wales. Support services for homeless people, particularly single people, have largely been provided by third sector organisations working outside the statutory system. This makes them vulnerable to competing agendas, particularly those with statutory backing. This has been the case in England where the ring-fence for the Supporting People funding was removed in 2009. This funding was predominantly used to finance homelessness services for people who do not qualify as statutory homeless. Since 2010, Supporting People funding in England has decreased by 67 per cent. The Welsh Government’s decision, to merge Supporting People with a wider series of non-housing grants and remove longer-term certainty about the funding level, presents a similar risk. This decision has provoked widespread concern from the sector.

Solution

All support services and budgetary provision for rough sleepers must be protected by both national governments. This is needed to guarantee the support they need to access and maintain tenancies. It is also needed to protect the budgets for these crucial services, which have proven vulnerable to cuts.

As outlined in Chapter 13 this duty would primarily be placed on local authorities. Furthermore, the Welsh Government should maintain a ring-fence between housing-based grants and non-housing grants and provide certainty of at least two years in setting the level of the housing grant. This is to assist with planning and commissioning the longer-term support needed to help homeless people.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster and Welsh Governments.

Problem

A key problem identified by those working in the homelessness sector is how outreach teams can identify particularly vulnerable groups. These groups are often less visible and might include women and younger rough sleepers.

In 2012, the StreetLink programme was set up in England and Wales to help the public identify rough sleepers and connect them to local services. StreetLink allows people to report that they have seen a rough sleeper via a website, mobile app and phone line. This is a key mechanism by which outreach teams in England and Wales receive information about rough sleepers’ locations.

StreetLink is funded by the MHCLG, the Greater London Authority (GLA) and the Welsh Government. It is delivered by Homeless Link in partnership with St Mungo’s.

The recent evaluation of StreetLink found that it is being used regularly by a variety of different groups in addition to members of the public for whom it was originally designed. These include: rough sleepers themselves who self refer; homelessness organisations who refer their clients; other organisations where homeless people might refer (eg food banks), and even local authority Housing Options teams to refer people who present as homeless to them too.

Most members of the public who have used StreetLink in England and Wales view StreetLink positively. They believe it is a quick and easy way for members of the public to connect a rough sleeper with relevant local services. However, the perception of StreetLink among those homeless people who have used it to self-refer in England and Wales is less positive.

Solution

The MHCLG, GLA and the Welsh Government should increase investment in StreetLink across England and Wales to help expand the public’s role in identifying rough sleepers.

Using the evaluation findings, we recommend the following to further promote the use and understanding of StreetLink. This will ensure there is sufficient resource to set up a separate helpline for homeless people and those working with this group.

The StreetLink service does not currently operate in Scotland. We recommend that, using the evidence in England and Wales, the Scottish Government undertake an evaluation to explore whether it would be a useful mechanism to help identity and reduce the number of people sleeping rough.

Impact

Greater investment in the StreetLink services, which would lead to an increased number of rough sleepers identified by the public, must therefore be accompanied by greater investment in street outreach teams. More detail on the expansion of outreach services is outlined elsewhere in this chapter.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments.

Problem

While the shift to a housing-led, rapid rehousing approach is a key element of this plan to end homelessness, we should never allow the provision of good quality emergency accommodation to be withdrawn. Over time, it is reasonable to suggest that hostels and other emergency accommodation will be scaled back. However, there will always be a need for short-term and high-quality emergency provision.

Some supported housing schemes, especially those with high levels of wear and tear such as hostels, can have considerably higher costs than mainstream accommodation in social or private rented sectors. The introduction of Universal Credit means that these higher costs would need to be managed within a centralised system.

The design of Universal Credit also makes it too inflexible to respond to short stays in supported accommodation. As a result, during 2017/2018 the Westminster Government is undertaking a Great Britain-wide consultation about the future funding of supported housing.

At the time of writing, proposed changes to funding for short-term supported housing will transfer the rents and eligible service charges into a ring-fenced pot. This will be administered by local authorities and will include very short-term emergency accommodation, and all supported housing with an intended stay of less than two years’ duration.

Crisis is concerned that this will reduce funding available over the long term, should the ring-fence be lost in future. It will also reduce the ability of providers to raise finance to invest in improving or maintaining the quality of existing services, or building new supply. There are concerns that good quality short-term accommodation for homeless people could be lost and as a result initiatives to end rough sleeping undermined.

Solution

Rather than introduce major changes to the funding of short term supported housing, the Westminster Government should ensure the design of the Universal Credit system is flexible and responsive enough to meet the needs of people in supported housing and fully take account of supported housing costs.

Any future consideration of funding for supported housing should be undertaken as part of a housing and homelessness focused strategic review. Once the Westminster, Scottish and Welsh Governments have consulted upon and agreed future plans for tackling homelessness, their funding strategies should reflect these.

Impact

This should see less demand and need for short-term supported housing. Better prevention services and housing-led approaches result in people receiving the support they need in mainstream accommodation.

Responsibility for change

Homelessness and housing policy are devolved matters – but welfare is a UK-wide led policy.

The Westminster Government should take responsibility for ensuring Universal Credit is compatible with the short-term supported housing sector and fully meets the associated housing costs. This will ensure people needing short-term supported housing are not discriminated against through reliance on local councils covering their housing costs. They should be able to pay their rents in the same way as other citizens. This should happen immediately.

Each government should adopt a plan to move towards a housing-led approach to preventing and tackling homelessness. The Scottish, Welsh and Westminster Governments should work together to develop the funding systems needed to support the delivery of strategic, integrated and holistic housing-led services to ensure homelessness is rare, brief and nonrecurrent.

Problem

Outreach teams often try to reconnect a rough sleeper back to the local authority area where they had their last settled base so they can reestablish a local connection. This policy expanded rapidly in England after the introduction of NSNO. It should be noted that this policy is far more common in England and Wales. In Scotland, housing support for rough sleepers is provided through the statutory local connection framework.

When done poorly, reconnections can be detrimental to rough sleepers. The area where the person has the connection may not be appropriate to them anymore. There might not be a support network or they may be threatened with violence if they return.

A 2015 Crisis-commissioned report found while the policy of reconnecting rough sleepers is widely used, outcomes are often not monitored. Too often people are reconnected to somewhere they have no meaningful connections or support services in place. The limited data available suggests that reconnection experiences and outcomes vary dramatically. They can be positive where someone is found accommodation with the support they need. Or they can be negative – where someone may have to sleep rough in the connection area because the services offered are poor or time limited.

Evidence from the ‘what works’ review, found that reconnections are much more likely to be successful for people who are new to the streets. This is because they might still have a live connection in the area. Reconnection is also successful where the connecting authority ensures there is meaningful support on offer at the destination before the person travels there.

Solution

Governments in each nation should introduce a national reconnections framework.

Reconnections should only be explored when rough sleepers have a meaningful connection to an area. This means prior use of services and/ or the presence of positive social support networks. Ultimately, the decision should be based on individual choice. A reconnection should not be explored if there are grounds to believe that returning to the area where they were last settled will put someone at risk of violence or harm. This should be regardless of whether there are police records to prove this.

Standards should be applied to the reconnection approach via the establishment of national reconnection frameworks in each nation. These national standards should outline the minimum level of support rough sleepers should receive from the host and recipient local authority, and from other third sector agencies. They should also include a description of when it is and is not appropriate to reconnect a rough sleeper. This should include details of how to assess security of accommodation at the destination, protocols for escorting people safely, and periodic checks between authorities regarding the outcomes of people who have been reconnected.

National reconnections frameworks should also require local authorities to collect and publish data on the reconnections they make and receive. Long-term outcomes for people relating to sustaining settled accommodation and their health and wellbeing should be included.

Impact

The production of a national reconnections framework and collection of and publication of data on reconnections could be achieved relatively quickly without legislative change. Local authorities would require some additional funding to help collect more data on reconnections.

Responsibility for change

National governments in England, Scotland and Wales.

Problem

Rough sleeping is dangerous, and every effort should be made to find immediate accommodation to prevent and stop it happening. Where people have to prove a local connection to an area this can stand in the way of rough sleepers accessing statutory homelessness services.

In England and Wales, the requirement to demonstrate local connection can also limit access to the nonstatutory services such as emergency accommodation and day centres. And even if they are in the area to which they have a local connection, some rough sleepers will simply not have the paperwork to prove it.

Solution

Until local connection is more widely reformed, so it no longer presents a barrier to assistance for anyone at risk of homelessness, it should be scrapped for rough sleepers.

To get immediate help to access accommodation with the necessary support, rough sleepers should not face an arbitrary test to prove local connection, and so this rule must be scrapped. This does not, however, rule out responsible reconnections, where a rough sleeper will choose to return to a place with better support.

In Scotland, local connection is currently applied to accessing settled accommodation, but the power to suspend local connection altogether has already been created and should now be put into effect. This has also been a key recommendation of the Homelessness and Rough Sleeping Action Group in Scotland. Chapter 13 sets out the case for reform of local connection across Great Britain in more detail.

Impact

This change would significantly improve entitlements for rough sleepers providing local authorities have the resources needed to accommodate and support people. Certain ‘hotspot’ local authorities will be disadvantaged by this change.

Westminster is an example of a London borough that has a rough sleeping population largely made up of people from outside. Proportionate funding will therefore be needed in such areas, ideally through a system where funding support follows the individual rough sleeper.

In theory, this policy would be cost neutral. Although before implementation, national governments should investigate whether it is more likely that services will be accessed in local authorities with higher running costs. This could result in a higher than average bill for some ‘home’ or ‘last settled base’ authorities whose services are significantly lower to run than Westminster’s for example.

Responsibility for change

The Westminster, Welsh and Scottish Governments.

Problem

The Vagrancy Act (1824) is pre-Victorian era piece of law that is still used to criminalise people who are rough sleeping in England and Wales. This is unacceptable and not just because the punitive values of this approach are out-dated. There is also good evidence showing that enforcement approaches are not an effective way to either engage rough sleepers, or to resolve their problems.

The growth of enforcement measures against rough sleepers in recent years been met with significant opposition from the public. Our recent research in England and Wales found well-targeted enforcement, with genuine offers of accommodation and support, can act as a catalyst for helping rough sleepers away from the streets.

However, if used in isolation this approach can merely displace rough sleepers, leaving them further marginalised and excluded from the help they need. Prosecuting people for the ‘crime’ of rough sleeping is far beyond the evidence of what will effectively assist people.

While the use of informal enforcement measures is much more common, evidence shows that The Vagrancy Act (1824) is still used to clear rough sleepers from the streets. The Act gives the police in England and Wales the power to issue a formal arrest if someone has been offered shelter and continues to sleep on the street. It not only targets behaviour potentially linked to rough sleeping, but the very act of rough sleeping itself. Begging and persistent begging are also prohibited through the Act. A recent Freedom of Information request found that the number of prosecutions under section 3 of The Vagrancy Act (1824) increased from 1,510 in 2006/07 to 2,365 in 2015/16 in England.

Solution

Criminalising rough sleepers does nothing to help resolve and tackle the causes of homelessness. It is far more likely to prevent someone from accessing vital services that support them to move away from the streets.

We recommend that the Westminster Government repeal The Vagrancy Act (1824).

Impact

Repealing the Act would mean that rough sleeping alone could not warrant criminal prosecution. This would improve the chances of rough sleepers rebuilding their lives once they move off the streets.

Furthermore, repealing the Act would have a significant impact in helping to more positively shape the attitudes of enforcement agencies and the police. This should ensure that where other enforcement measures are used, there is a greater awareness about the need to provide support in parallel with helping someone end their homelessness.

There would be no significant cost implications.

It should be noted that anti-social behavioural problems linked to rough sleeping and begging could still be enforced against using newer pieces of legislation. For example, The Antisocial Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act (2014) provides the police with a range of options to take enforcement action against individuals or groups causing, or likely to cause, antisocial behaviour in public places or common areas of private land. The Vagrancy Act (1824) can also be used to enforce against indecent exposure. This offence however, can now be enforced against under The Sexual Offences Act (2003).

Responsibility for change

The Westminster Government.

Problem