Politicians, police & charities urge government to scrap Vagrancy Act

19.06.2019

Report from Crisis includes new legal review of the Act that finds it ‘obsolete’

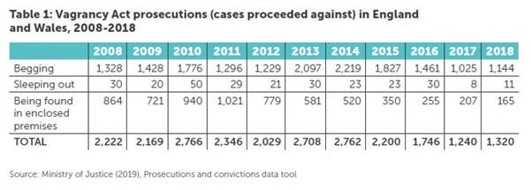

FOI reveals there were 1,320 prosecutions under the Act in 2018

The centuries-old Vagrancy Act, which makes rough sleeping and begging illegal in England and Wales, should be scrapped because it is needlessly pushing vulnerable people further from help, according to a new report from homelessness charity Crisis. The calls come as the Government today announces its review of the Act as part of its rough sleeping strategy.

Leading figures from across the political spectrum and the police, including former Met Commissioner Lord Hogan-Howe, have joined Crisis and a coalition of charities to call for the repeal of the Act¹, branding it out of date, inhumane and unfit to deal with the modern challenges of addressing rough sleeping and begging. [see quotes from Lord Hogan-Howe, police officials, case studies and politicians below]

The Vagrancy Act (1824) was originally brought in to make it easier for police to clear the streets of destitute soldiers returning from the Napoleonic Wars. It makes it a criminal offence to ‘wander abroad’ or to be ‘in any public place, street, highway, court, or passage, to beg or gather alms’ in England and Wales.² Nearly two hundred years later, it is still being employed, despite criticism from within the police force that it needlessly criminalises vulnerable people.

“It is extremely rare for people to make an informed decision to be homeless, and many people living without shelter have complex needs: they may be fleeing abuse at home, may struggle with addiction, and/or suffer from poor health. To criminalise this seems, well... criminal! – An anonymous Chief Inspector of an English police force

While some police forces are reluctant to employ it, new figures obtained under a Freedom of Information request from the Ministry of Justice reveal “It is extremely rare for people to make an informed decision to be homeless, and many people living without shelter have complex needs: they may be fleeing abuse at home, may struggle with addiction, and/or suffer from poor health. To criminalise this seems, well... criminal! – An anonymous Chief Inspector of an English police forceit is still very much in use. There were 1,320 recorded prosecutions under the Vagrancy Act in 2018, an increase of 6% on the previous year, but less than half the number made five years ago.³ Rough sleeping in England has increased significantly between 2014 and 2018, rising by 70% in England, in the same period, suggesting the Act is not the most effective tool for dealing with rough sleeping.

While prosecution numbers have fluctuated, previous evidence has shown that rough sleepers are far more frequently victims of informal use of the Vagrancy Act (and other powers) to move them on or challenge behaviour without formal caution or arrest. This kind of approach causes frustration among the people affected, including support and outreach workers and some police themselves, given that these approaches do not address the root causes of the situation. It is rarely accompanied by signposting to services and simply serves to push people into more dangerous places, riskier activities, or into a criminal justice system that is not well designed to address their needs.

“Since coming to Blackpool I’ve now had thirteen charges under the Vagrancy Act, and I’ve also been taken to court twice for it. Five of those warnings I was even asleep when they gave them to me, so how could that have been for begging? I just woke up to find it on my sleeping bag.

“Half the homeless in town have been given Vagrancy Act papers now, and most of them have been fined about £100 and then given a banning order from the town centre. If they get caught coming back, they get done again and could go to jail, but that means all those people can’t get into town to use the few local services there are for rough sleepers. When the SWEP [severe weather emergency protocol] came into place during the winter those people couldn’t get into town to use the emergency shelters because of those banning orders.” Pudsey left care at 15 and ended up on the streets because he had nowhere else to go. He came to Blackpool in April 2018 to make a new start

As well as attracting criticism from law enforcement agencies and those affected by it, the Act has also been found to have little practical use. A review of existing legislation conducted as part of Crisis’ report found the Act to be ‘obsolete’ given the alternatives available to police. Laws including the anti-social behaviour act of 2014 are cited as being a more appropriate way of addressing activity like aggressive begging, while senior figures from the police agree the solutions to rough sleeping lie in helping people away from the streets, something they are not best placed to do.

“The Vagrancy Act implies that it is the responsibility of the police alone to respond to these issues [rough sleeping and begging], but that is a view firmly rooted in 1824. Nowadays, we know that multi-agency support and the employment of frontline outreach services can make a huge difference in helping people overcome the barriers that would otherwise keep them homeless.” - The Lord Hogan-Howe QPM, former Metropolitan Police Commissioner

Crisis is calling for the Vagrancy Act to be repealed immediately. England and Wales are among the few countries left to continue to uphold vagrancy laws and can learn from countries that have repealed them⁵ - the Vagrancy Act was abolished in Scotland in 1982, where additional legislation was created to deal with anti-social and criminal behaviour.

Regarding the approach to homeless, vulnerable and destitute people, the report makes clear that rough sleepers need help from dedicated outreach teams that’s allied to offers of stable accommodation and meaningful, long-term support.

Jon Sparkes, Chief Executive of Crisis, said: “The continued practice of criminalising homeless people under the Vagrancy Act is a disgrace. There are real solutions to resolving people’s homelessness – arrest and prosecution are not among them.

“Of course, police and councils must be able to respond to the concerns of local residents in cases of genuine anti-social activity, but we need to see an approach that allows vulnerable people access to the vital services they need to move away from the streets for good.

“The Government has pledged to review the Vagrancy Act as part of its rough sleeping strategy, but it must go further. The Act may have been fit for purpose 200 years ago, but it now represents everything that’s wrong with how homeless and vulnerable people are treated. It must be scrapped.”

ENDS

For further information, including a copy of Crisis’ report, ‘Scrap the Act: A case for repealing the Vagrancy Act (1824)’ or to arrange a spokesperson interview please email simon.trevethick@crisis.org.uk or call 0207 426 3880 (in working hours) or 07973 372587 (out of hours).

Notes to editors

Crisis’ campaign partner charities are: Centrepoint, Cymorth Cymru, Homeless Link, Shelter Cymru, St Mungo’s and The Wallich. For a full list of all campaign partners and supporters visit www.crisis.org.uk/ScraptheAct

1. Further support for the scrapping of the Vagrancy Act:

Karl, a former rough sleeper from Liverpool who is now permanently housed thanks to Crisis, said: “Arresting people for being homeless only made them stay homeless. You felt like a criminal, so you end up shutting down and just relying on the homeless community instead. It becomes learned behaviour. I tried my best to stay out of sight.

It would be brilliant if the Vagrancy Act could be repealed. That would help turn public opinion back to helping homeless instead of punishing them. People always says it’s complex to end homelessness. But it’s not. It’s only complex for homeless people living on the streets. The solutions to solve it are already there.”

A Chief Inspector of an English police force who wished to remain anonymous said: “We joined the job to help people who are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, and the homeless community are more likely to be victimised owing to their housing status than other members of our communities. We have a duty to protect them as vulnerable adults in our community. We are asked to consider how we prioritise our scant resources according to threat, risk and harm. But with begging, where's the threat? Where's the risk? Where's the harm?”

David Jamieson, West Midlands Police and Crime Commissioner: "I am concerned about the use of the Vagrancy Act. I am pleased that it is being used less and less, but I now think it is the time for the government to remove it from the statute books and update the legislation. It should be replaced with legislation that helps agencies to work closer together to ensure no-one falls through the cracks.”

Tracey Crouch, Conservative MP for Chatham and Aylesford, said: "It is long past time that this outdated piece of legislation was retired, and I am pleased that the Government has made a commitment to review it. All the evidence shows that it is doing nothing to help vulnerable homeless people and is simply out of step with more modern legislation. I strongly urge that it be repealed as soon as possible, so that we can move away from blunt enforcement measures and instead focus on providing the joined-up services that will make a real impact on rough sleeping."

Alex Cunningham, Labour MP for Stockton North and Shadow Housing Minister, said: "Labour does not support criminalising rough sleepers and that is why we have already made a commitment to repeal the Vagrancy Act as part of our plan to eradicate rough sleeping within five years of a Labour Government. I strongly urge the current Government to do the right thing and get rid of this inhumane and completely unhelpful piece of legislation without delay.”

Layla Moran, Liberal Democrat MP for Oxford West and Abingdon, said: “Being homeless should not be a crime. We need to do more to help homeless people, tackling the issues compassionately at their root, not demonising them via the criminal justice system.

"While Brexit has dominated the headlines, the Liberal Democrats and I have been fighting this campaign for over a year, after students in my constituency started a campaign.

"It's time that we scrap the cruel and outdated Vagrancy Act, which is still used frequently on our streets today, and seriously confront the issues of homelessness in our society."

Liz Saville Roberts, Plaid Cymru MP for Dwyfor Meirionnydd, said: “The Vagrancy Act is an outdated piece of legislation, which was aimed at tackling homelessness following the Napoleonic wars.

“Jump forward two hundred years and it is still used today to penalise people for sleeping rough or begging. It is a cruel and draconian piece of legislation which serves only to punish those who have the least; those forced into destitution through no fault of their own.

“Those pushed into homelessness should be treated with respect and dignity and afforded support and encouragement. Instead the Vagrancy Act stigmatises some of the most vulnerable in society. It must be repealed.”

2. The Vagrancy Act 1824 remains in law across England and Wales and is still in use today. It has been subject to a number of amendments but, as it stands, has two main sections that police can use against people suspected of offences:

Section 3 of the Act: begging and persistent begging are prohibited through the Act: ‘Every person wandering abroad, or placing himself or herself in any public place, street, highway, court, or passage, to beg or gather alms’. An amendment in 1935 provided that people could also be arrested if there is a shelter nearby that can be accessed or if they have been offered a shelter and still sleep on the street. Section 3 is a recordable offence and the maximum sentence is currently a fine at level 3 of the standard scale (currently up to £1,000).

Section 4 of the Act: ‘Wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air, or under a tent, or in any cart or wagon, and not giving a good account of himself’.

There is also an offence for ‘being in enclosed premises for an unlawful purpose’, which is used, for example, when dealing with people suspected of burglary when apprehended by the police. However, it is also sometimes used to challenge people who are sleeping rough.

3.

Begging is the most prosecuted offence under the Act, with around 1,000 prosecutions in 2017. While this represents a low in more recent terms, it has fluctuated over time. In the late 1980s and early 1990s the figures were around 1,500.[1] The current level of begging prosecutions is on a par with the early 1970s and the early 1980s, but it is much higher than earlier decades, such as the 1950s and 1960s.[2]

Prosecutions for ‘sleeping out’ are low, with only 11 in 2018, but there was a peak in 2010, when there were 50 prosecutions.[3] They were last at this approximate level during the mid to late 1980s (there were 9 prosecutions in 1986, 14 in 1987 and 13 in 1988, and 24 in 1989). Use of the Act continued to be uneven, however. In 1989 specifically, for example, half of sleeping out prosecutions were in London and there were no recorded prosecutions in Wales.[4]

Prosecutions for ‘being found in enclosed premises for an unlawful purpose’ were at 207 in 2017, but also peaked most recently around 2011 at just over 1,000.

While rough sleeping increased significantly between 2014 and 2018, rising by 70% in England,[5] prosecutions under the Act declined. This suggests that the Act is not the primary tool for dealing with rough sleeping.

4. Previous Crisis research across local authorities in England and Wales found that, while seven out of every 10 used enforcement action of some type, only about half of these areas used section 4 of the Vagrancy Act (34 per cent of local areas used it) in 2017, which includes the offences of ‘sleeping out’ and ‘being found in enclosed premises’[6]

5. Other nations that previously had vagrancy laws that have repealed them:

· In the USA a succession of city and regional vagrancy laws were ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court in the early 1970s, starting with a Florida case in 1972.

· The Canadian Ministry of Justice has legislation in the Parliament to repeal a number of laws that had been struck down in courts but remained in law, including a diverse list of outdated laws such as vagrancy.[7] The list was dubbed the “zombie laws” by Canadian legal experts.

· Belgium abolished its laws against vagrants and begging in 1993 that had been in place since 1891. There are some relevant offences still in place but they are restricted to ‘aggressive’ begging.

· Finland’s 1883 vagrancy law was repealed in 1987.

[1] Home Office Criminal Statistics England and Wales annually 1970-1980 (London, various) and Hansard: HC Debs 1980-1992

[2] Home Office Criminal Statistics England and Wales 1952 (London: July 1953) Cm 8941, Home Office Criminal Statistics England and Wales 1958 (London: July 1959) Cm 803, Home Office Criminal Statistics England and Wales 1960 (London: July 1961) Cm 1437, Home Office Criminal Statistics England and Wales 1964 (London: November 1965) Cmd 2815

[3] Ministry of Justice (2018), Criminal Justice Statistics

[4] 1986 figure from HC Deb 16 Nov 1989 vol 160; 1987 and 1988 figures from HC Deb 24 January 1990 vol 165 c714W; 1989 figure in HL Deb 22 May 1991 vol 529 cc12-3WA

[5] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2019), Rough Sleeping Statistics Autumn 2018, England (Revised), 25 February 2019 (revised)

[6] Sanders, B., & Albanese, F. (2017). An examination of the scale and impact of enforcement interventions on street homeless people in England and Wales, London: Crisis, p.15. Note that approximately another third of areas asked either did not respond or did not hold the data.